7 (Mostly Terrible) Ideas to Shake Up Charity Funding

Right now, charity funding in the UK feels like watching a much-loved first car slowly fall apart. Bits are starting to fall off, it doesn't run quite as smoothly as it used to, and some of the parts have given up completely. But no one can afford a replacement, and we very much need it to keep working so we can still get to work.

Funds are shutting down or "pausing", demand for charity services is higher than ever, and increasing numbers of applications are causing real problems for people giving out money.

Though in amongst all this, there's still a lot of innovation going on. Perhaps with necessity as the mother of invention, funders and commissioners across the country are still open to experimenting with new ideas.

We've seen suggestions of:

- Randomised grant awards

- Participatory grant making / budgeting

- Social Impact Bonds

- Building endowments in local charities

- Specific local or digital infrastructure funds

As a bit of a thought experiment, we want to suggest even more alternatives. So here's 7 left-field proposals for a new way to fund local community work:

1. The Secret Millionaire / Mystery Shopper:

Every Central and Local Government Department spends a huge portion of its budget on a tiny number of people. These people typically have complex support needs that cut across multiple parts of Government – from social care, to the NHS, to the police and court system. Often hundreds of thousands of pounds can be spent over the course of multiple decades bouncing people back and forth from assessment to assessment, never actually getting the real support they need.

We propose a radical solution, adapted from a noughties Channel 4 reality show:

Pick 1 person (almost at random). Give them a ludicrously large personal budget – maybe something like £500,000 / year. They're allowed to spend that money on any kind of support they need, with the condition that the support becomes available to other people like them through local charities.

Why would you do that?

- Desire Line Architecture - Just as urban planners sometimes wait to see where people naturally walk before paving paths, this approach reveals the actual paths people would take through services if friction was removed. Unlike top-down service design, it exposes genuine user preferences when all options are truly available.

- Leverage Through Precedent - Once a solution is created for the funded individual, it becomes much harder for the system to claim it's impossible for others. While typical advocacy can be dismissed with "it's more complicated than that," a working example forces the system to explain why what's possible for one isn't possible for all.

- Defensive System Judo - The high-profile nature and unlimited budget flips typical system dynamics. Instead of services trying to deflect complex cases, they're incentivised to engage to avoid embarrassment and potential precedent-setting workarounds. It's like having a VIP patient in a hospital - everyone suddenly becomes solution-oriented, similar to how Jeff Bezos used to forward customer emails to his team with just a single question mark.

The downsides

There are extremely obvious downsides. For one, it's incredibly unfair to everyone who's not picked, and secondly you might pick someone who makes terrible decisions.

But the most interesting problem I can see is that the focus on one individual's journey might obscure systemic issues that only emerge at scale. Like how a mystery shopper can't detect problems that only arise during rush hour, some system failures might be invisible when viewing a single enhanced journey.

Still, it might teach us something interesting.

2. The No-Return Nomination:

The charity sector can be very competitive. It's not the sector's most attractive face, but when it comes to bidding for limited funds in a local area, almost by necessity, it's unfortunately pretty common. But in actual service delivery, charities have to work together, whether that's to share physical space or to refer clients to each others' services.

To address this, why not try a new kind of grant application process?

How about this: organisations apply for core funding, but they can only apply for a different organisation. And to stop obvious "you scratch my back, I scratch yours" gaming of the system, you can't nominate someone who's already nominated you.

Why would you do that?

- Competitive Empathy - It creates a system where understanding other organisations deeply becomes a strategic advantage. Unlike traditional funding where organisations get better at writing about themselves, this system rewards those who best understand the ecosystem's gaps and others' strengths.

- Invisible Asset Surfacing - Organisations often know about valuable but under-recognized peers in ways funders never could. Similar to how start-up founders can make very good Venture Capital investors, this system taps into insider knowledge of who's actually driving impact without formal recognition.

- Co-operation Arbitrage - Organisations realise they can increase their chances of receiving funding (via others' nominations) by being genuinely helpful to peers. This creates incentives where investing in others' success becomes rational self-interest, rather than just rhetoric.

The downsides

There's a few obvious ones – like how people might game the system to set up nomination rings, or how it might be administratively difficult to keep track of who has nominated whom.

But possibly the more interesting problems would be around the kinds of organisations that would still fail to get applications through, or whether the applications would be suitable.

Funders do a lot of work on the due-diligence of organisations or projects – that's likely to be a lot trickier when organisations themselves aren't the ones applying.

3. Community Tenure:

A massive issue for the current mechanism of charitable funding is how uncertain it can all be. Short-term projects, changing funder priorities, and finely balanced budgets mean long term planning is basically impossible. But it also creates dramatic power imbalances: funders with endowments and charities working to meet payroll every month, are on a far from level playing field.

What if we copied the idea of "tenure" from academia?

What if funders were to find highly motivated, well-trusted individuals in a local community, and permanently "endow" them, as a single person. Just like professors, this person could have a guaranteed annual salary, with very few strings attached.

Obviously this has been touched on, with things like Year Here fellows or Newspeak fellows, but this would be taking it further, allowing someone to work on a much more permanent basis.

Why would you do that?

- Cultural Memory Banking - Similar to how tenured professors preserve academic traditions, these individuals naturally become repositories of community history and relationships. But unlike academics who document formally, they maintain the subtle, lived knowledge of how the community actually works - who knows whom, which approaches have failed before, which tensions need managing.

- Entrepreneurial Safety Net - The guaranteed income creates space for community members to take on ambitious, slow-burning projects that most people can't risk. While academic tenure enables decades-long research, community tenure enables decades-long relationship building and system-changing work that typical grant cycles don't support.

- Professional Troublemakers - The financial independence allows these individuals to become constructive critics without fear of retaliation. Unlike academics bound by disciplinary norms, they can freely cross sectors, call out problems, and experiment with solutions regardless of institutional preferences, and sitting outside existing power dynamics.

The downsides

The main drawback is again pretty clear – you need to pick the right person(s). But assuming you do that, probably the biggest remaining issue is that recipients might unintentionally become gatekeepers, with their long-term presence and relationships making it harder for new voices to gain influence.

4. The Brewster's Millions Fund:

For the uninitiated, this is based on a book/film with a simple premise: a man has 30 days to spend $30 million (in 1985 dollars, so basically infinity money now), but is not allowed to own any assets, destroy the money, gift it or give it to charity.

This slightly ridiculous idea is to do that, but for charitable funding. To set up a fund that from announcement, through disbursement, to spending, takes something like a fortnight, and isn't allowed to end up with any tangible capital assets. And you do this at an entirely random time, not associated with any particularly notable event.

Why (on earth) would you do that?

- Emergency Dry-Run - It's surprisingly difficult to give out money quickly. Every time there's an emergency or crisis, distributing funds rapidly becomes an issue, running into problems like capital disregards for people claiming benefits, or potential PR risks that result from misallocation. Creating an entirely artificial deadline, might be a good dry-run, like a chaos monkey in software applications.

- Process Improvements - Like how emergency room doctors make better decisions by having to make them quickly, forcing rapid deployment eliminates overthinking and bureaucratic layers. While traditional funders might spend months debating optimal strategies, this model forces funders to try out more streamlined approaches, that might then work for other funds.

- Attention Surge - The dramatic time pressure might create a brief period of intense community focus that might bring in matching resources. Similar to how disaster response mobilises dormant assets, rapid spending could unlock otherwise unavailable resources, volunteers, and permissions.

The downsides

As much as I enjoyed Brewster's Millions (the film), it got pretty terrible reviews. It's a pretty stupid idea, and I really can't imagine any normal funder signing off on it when funding is so hard to come by.

But if anyone ever wins the lottery and wants to do something stupid, it could be fun.

5. "Buy Dirt":

From no assets to just assets.

Perhaps we should resurrect an old method. Instead of providing grants to fund ongoing operations, maybe funders should just start buying land, to host community organisations at zero or peppercorn rent. After all, they're not making it anymore.

Funders could choose to buy up large amounts of land or buildings as the primary way of supporting a community, likely in partnership with something like a community land trust.

Why would you do that?

- Gentrification Shield - By acquiring properties early, the foundation can act as a protective barrier against displacement, essentially freezing portions of the community in place even as market pressures increase. This provides long-term stability that annual grants can't match.

- Accidental Collaboration - When a foundation owns key buildings, it creates natural collision points where different community groups must interact and coordinate. Unlike grants which can inadvertently create competition between community groups, shared physical spaces often force cooperation.

- Mission Stability - Real estate ownership protects against future boards or leaders drifting from the original mission. While future leadership could redirect grant money to new priorities, it's much harder to repurpose buildings that are physically embedded in specific communities.

The downsides

Again, this is pretty obvious, but at a time of extremely high land prices that cause huge problems for young people (and others) paying for housing, maybe it's not a great idea to put even more upwards pressure on the property market?

And perhaps this strategy, while being quite good for stability, if society or the area changes, will have the classic side effect of entrenching resources to serving yesterday's problems with yesterday's solutions.

6. Section 106 for everything:

Apologies, this might be a bit niche.

When developers are looking for planning permission to build new houses, they often have to come to a Section 106 agreement with the Local Authority. Part of this often takes the form of spending money in the local community, to mitigate any of the negative consequences of a new development.

We already have something of a precedent for giving money to charity to expunge your violation of a social norm. Like a modern kind of a Medieval Catholic Church indulgence, we often use charitable donations as a way of buying public forgiveness. For example, when the banks were fined for the Libor fixing scandal, the money ended up going to charity.

So why not do something more proactively?

There's a lot of things we've collectively decided we don't want people to do – kill badgers on your land, drive faster than a speed limit, have loud parties that go on into the night or having a wood burning fire in Central London.

Instead of just banning them, let's have a simple rate card of charitable donations required to be allowed to do it.

Why would you do that?

- Speed of funds - Compared to more traditional fines which often sit in government accounts or get tied up in legal processes, this system immediately converts negative actions into community benefits. The moment someone wants to do something a bit dodgy, money starts flowing to counterbalancing social good.

- Resolving Uncertainty - Companies can make clearer business decisions and communities can get predictable benefit streams. Unlike the current system where companies might risk fines/reputation damage and communities might get nothing, both sides can plan around known costs/benefits.

- Social Norm Price Discovery - The rate card effectively creates a live market showing how much communities really value different norms. If no one pays to violate certain norms even at low prices, it reveals true community red lines. On the flip side, loads of purchases at certain price points show which norms might be ready to be scrapped.

The downsides

Hmm, maybe putting a price on our basic social fabric, and very literally leaving one set of rules for the rich and one for everyone else.

Still, we basically do this already, it might be worth making it more transparent.

7. The Eradication Strategy

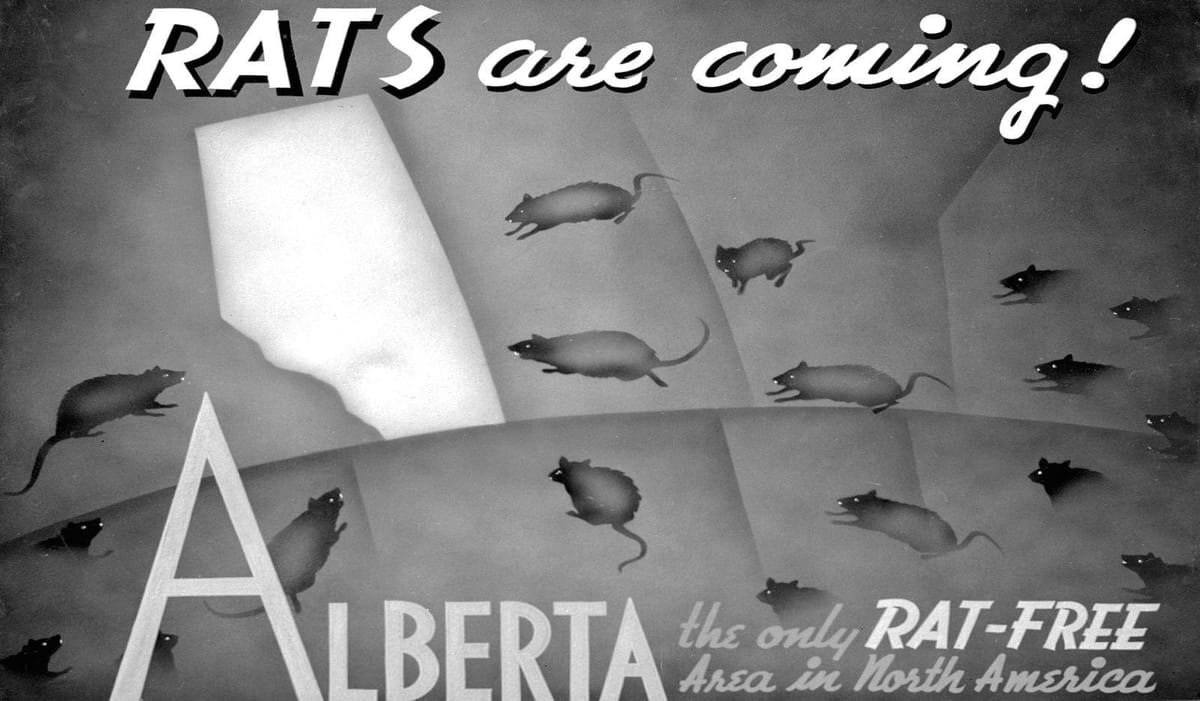

This is quite often used for diseases – completely eliminating smallpox, polio, river blindness globally, or things like malaria is specific countries (e.g. in the USA). But it's also used for animals, like rats in Alberta or the screwworm in America.

What if we tried this for other issues? What if we picked a very specific issue, and a small geographic area, and spent a large amount of money to completely eliminate it – say homelessness in Braintree, litter in Scarborough or food poverty in Llandudno.

Why would you do that?

- Circuit Breaking - Like disease elimination's focus on breaking transmission chains, a geographically concentrated approach can permanently disrupt local problem cycles. Homelessness services across the country might help individuals but maintain steady numbers, fully solving it in one town could break the specific local patterns that sustain the issue. Or in cases like litter, it could flip us to new social equilibrium, where the concept of littering becomes unthinkable, rather than commonplace.

- Social Proof Momentum - Success in one small area creates a powerful demonstrator that shifts from "managing" to "solving" being the default mindset. Similar to how smallpox eradication started with one village in India, a single litter-free river becomes a reference point that changes expectations about what's possible, so other areas might start to copy.

- Last Mile Lessons - The "last 10%" of people faced with things like poverty or homelessness, might have very different underlying causes and pathways out to the "first 90%". In a world where we're just trying to manage the level of an issue, we might never learn what works for these people, because we never even get to try.

The downsides

There's a few interesting potential issues:

- Problem Migration - success in one area might just displace issues to neighbouring areas without sufficient.

- Diminishing Returns – most obviously, solving something 100% might be many many times more expensive than a 90% solution. It's likely not to be the best use of funds.

- The Return of the Problem - if after the issues has been "eradicated", it just comes back straight away, it might be a lot of work for very little long term gain.

These ideas might go from potentially workable to stupid and deliberately provocative, but they all share one thing: they challenge us to think differently about how we fund community work. In a sector facing unprecedented pressures, perhaps the riskiest move is to keep doing things the same way.

There needs to be room for innovation in how we support our communities, and maybe some more extreme ideas might help point us in the right direction.