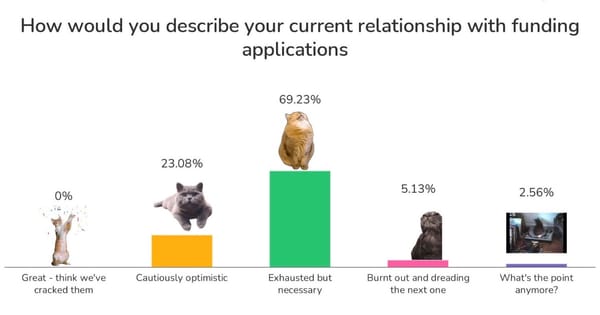

46% of grants cost more than they're worth

Every month we speak to charities frustrated with the difficulties of grant applications and reporting for their existing grants. Some organisations have raised the question of whether particular grants were even worth it? Would it have been better to just not apply? To answer that, we've got some numbers for you.

We wanted to estimate the "all-in" cost of a grant process - the time taken to apply, do impact measurement and other monitoring. We have also included the costs to the funder, the costs imposed on rejected applicants, and even the costs incurred by charities who decided not to finish an application. Including all these extra costs ("externalities"), means that even a grant that looks perfectly sensible for the organisation that receives it, could actually have cost the sector more in staff time than it received in money.

At this point, in many sectors, we would be at a loss - most companies don't announce exactly how they spend their money, but thanks to 360Giving and CharityBase we had really easy access to more information about funders and where their money goes. For the rest, our estimates are based on our experience of working with small charities (feel free to mentally adjust if you think we've got it wrong!).

Estimating the cost to funders

We know this section will get the least sympathy from people in cash-strapped charities, but it is an important consideration. The reality is that writing grant requirements, sorting through grant applications and visiting grantee organisations can be a lot of work. For sure, some do it better than others, but there is a very real cost to this exercise.

To do all this, you need to employ people. Fortunately for us, any foundation set up as a charity (i.e. all of them), lists their employees and volunteers with the Charity Commission. We looked at 29 of these foundations (chosen based on their reports to 360Giving). To get their total staff costs, we took employee numbers, and assumed that volunteers would work 1 day per week.

It turns out some funders have a lot more employees than others (don't worry, we've some more insightful things coming...). More interesting is the number of employees per grant delivered. If you exclude some crazy extremes - Camden Giving we're looking at you - there's not that much variation. Interestingly, we found that statistically, funder costs in grant making are driven more by the number of grants than the size of the grants.

So we assumed an average wage across funders (and their volunteers) of £30,000 per year, and then estimated the staff cost per grant for all 29 foundations:

Averaging across all of those funders, we got a final figure of £3,018 per grant. Because there's no need for false precision, we rounded that to £3,000.

So the first piece of the puzzle is complete, an average grant costs £3,000 just for the funder.

Estimating the cost to applicants

This is where things get more interesting, and a little bit less certain.

We looked at 3 types of "applicants" - organisations who received the grant, all organisations who finished the application, but also organisations who found the grant and decided not to submit an application.

Firstly, what is the cost to the organisation that received the grant? For the small charities we spoke to, we see that reporting and monitoring of a grant takes about a week. That includes preparing for a funder visit, collecting data on beneficiaries, describing your project, collecting case studies, working out "what you've learnt" etc. While some reporting requirements are seriously over the top, in general we estimate that reporting for a grant costs a charity £500.

But what about the organisations whose applications were unsuccessful? We need to know 2 things: 1) The time taken to apply to a grant and 2) The number of applicants for every grant.

For 1), we used the Grant Advisor website. Most grants take 2 days to apply for. We then found estimates for the number of applications per grant from 3 different funders: Esmée Fairbairn (7.4), the Henry Smith Charity (5.0) and Lloyds Bank Foundation for England and Wales (6.7). So, if there's 6 applications, each needing taking 2 days of work, at a day rate of £115, that's £1,380 spent on applying. We rounded that up to £1,400.

Finally, what about the people who didn't apply? Those who read through the guidelines, eligibility criteria and the application form, but never submitted. We've estimated (read: guessed), that for every applicant, there's 10 more who decided not to apply. (aside - if any funder wants to give us access to their Analytics, we'd be very happy to do this bit properly...) How long did these organisations spend on this process? We can't know for sure, but we have a good minimum estimate: how long does it take to read all the funding guidelines? We did some adding up...

Unless you're applying Camden Giving, it's going to take you 25 minutes to read the instructions. When you include discussing the grant with your colleagues, working out exactly if you're eligible, and starting some the application, that's probably ~2 hours even if you don't apply. So: £28.80 per organisation, across 60 organisations for every success, that's ~£1,700.

Adding everything up

The cost of everything put together is £6,600 per grant. Just under half of that cost is incurred by organisations that didn't end up getting a grant. 45% of the cost is incurred by the funder, and the remainder is imposed on the successful organisation.

46% of grants are likely a net loss

How does this "all-in" cost of £6,600 compare it to the distribution of all grants nationally? Again, from 360Giving, here's the distribution of all the 2018 grants:

More specifically, 46% of grants were less than our threshold.

Obviously, this calculation was done using best guesses and national averages. It would be a sensible and useful exercise for funders to evaluate this using their own data. In particular, accounting for the time cost of volunteers and time costs imposed on organisations who don't go on to receive a grant.

Now, having done this estimation of the problem, this feels like the time in the post where we suggest some solutions. But first, based on this analysis, we're going to suggest some things we don't think will work.

How not to improve things

We don't think this problem will come as a shock to many in the sector and there have been a lot of solutions thrown around to solve this problem. However, we don't think many of the most popular ones will work and here's why:

Firstly, accepting free-form applications - allowing charities to describe their programmes "in their own words". We don't like this idea. The first problem is that just under half the "all-in" cost is already incurred by the funder. Less structured and less comparable applications will only increase this. Secondly, a lot of charities aren't big fans of this approach either. What sounds like a good way to reduce the burden, actually just leaves charities trying to find out what the funder wants to hear through other sources - e.g. by calling or emailing. In our view, this 'solution' makes the situation worse at both ends.

The second suggestion is a "UCAS for charities" or a "single application form" for all funders. This sounds a lot more sensible, but we have outstanding concerns. Firstly, to stop universities being overloaded with applications, UCAS has restrictions on the number of universities a single student can apply to. But how are you going to limit charity applications? Students can only attend one university - charities have multiple funders. Secondly, a "single application form" works when everyone is looking for the same thing. However, if you want to apply to a place-based funder or a demographic-based funder, you don't want to force them to read through reams of information about projects irrelevant to them.

Finally, our single least favourite suggestion is asking charities to justify their own impact as a condition of receiving a grant (ie they do a lot of the funders work for them). There are organisations that do this properly, and it is a hugely expensive, difficult and time consuming process. Expecting small charities to do this kind of analysis is frankly unreasonable. It's our strong belief that at a small scale, you can use very simple measures at a fraction of the cost to achieve a substantial proportion of the long impact measurement process. For a grant of £5,000, do you really need a double-blind randomised control trial? Or could you just ask the local community centre how many people turned up to their project? Or whether they kept coming back?

Our actual suggestions:

As a funder, if you're not going to change the way you do your applications, reporting and monitoring: give bigger grants.

But, if you want to do smaller grants, that can target the 73% of charities with less than £100,000 income per year, you're going to need to be a bit different. The first step should be to make the application guidelines short, and somehow work out a way to give out a huge number of grants with hardly any staff. In our view, the second step involves replacing the application process with better reporting.

Exactly how to do that is a story for another day, but if you want access to the trailer, drop me an email at tom@plinth.org.uk.