HAF - the Sticking Plaster of the Future?

We all know that the Holiday Activity and Food Programme was hastily assembled to respond to a PR crisis. And it’s clearly not enough to solve deep-rooted issues of child poverty.

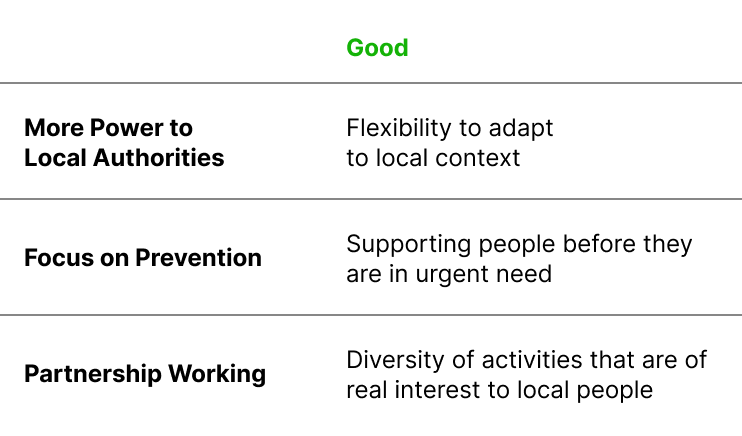

But from the chaos emerged an extremely interesting model:

- Trust in Local Authorities to manage the programme

- A prevention-based approach

- Partnership working with local organisations and infrastructure

This kind of model has thrown up some real problems, but if we can solve them, it could be a template for all kinds of other Government programmes.

I find it such an interesting model, that I’ve written 4,000 words on the topic…

HAF Programmes

HAF, the Holiday Activity and Food programme, provides activities and food during the holidays. It’s well named. It now happens across the whole country, providing these for children on Free School Meals.

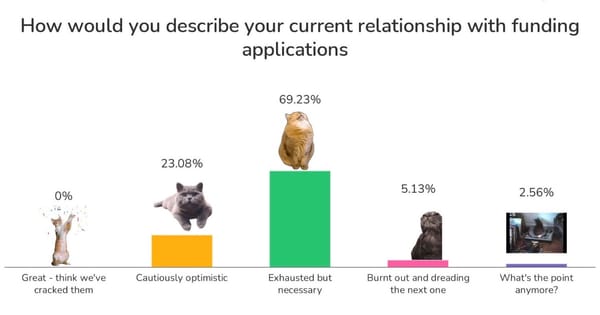

But its origins weren’t the most well considered. Its national rollout came from a last minute U-turn, built on a combination of solid data from a pilot scheme, long-term well-considered policy work from the Food Foundation, but mostly, some serious bullying from Marcus Rashford.

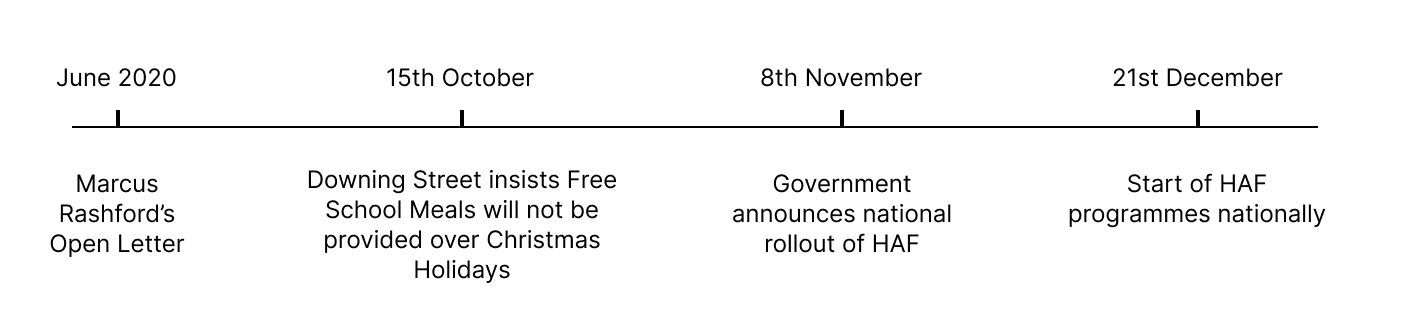

A representation of the process

This meant that the roll-out of the programme itself was extremely rushed, giving Local Authorities, schools and organisations providing activities just over 40 days to prepare for a busy holiday programme for the first time:

As a result of this time pressure, it was implemented in a pretty limited manner. It was only available for children on free school meals for 4 weeks of summer, and 1 week at Christmas and Easter. It provided no support for other weeks and other children not on free school meals who would have benefited from it.

It was clearly not enough to solve the wider issues of food poverty across the country. So it’s no surprise it was branded as a sticking plaster by many — a hasty attempt to tackle wider issues with a short-term intervention to address an immediate PR crisis.

We don’t disagree. But in our view, whether by luck or judgement, this “sticking plaster” has developed into a blueprint model for the future of public services delivery. In a world of increased Government centralisation, departmental siloes, continued austerity and decreasing state capacity, it stands out as a template for how service delivery can be decentralised, dynamic and maybe even inspiring.

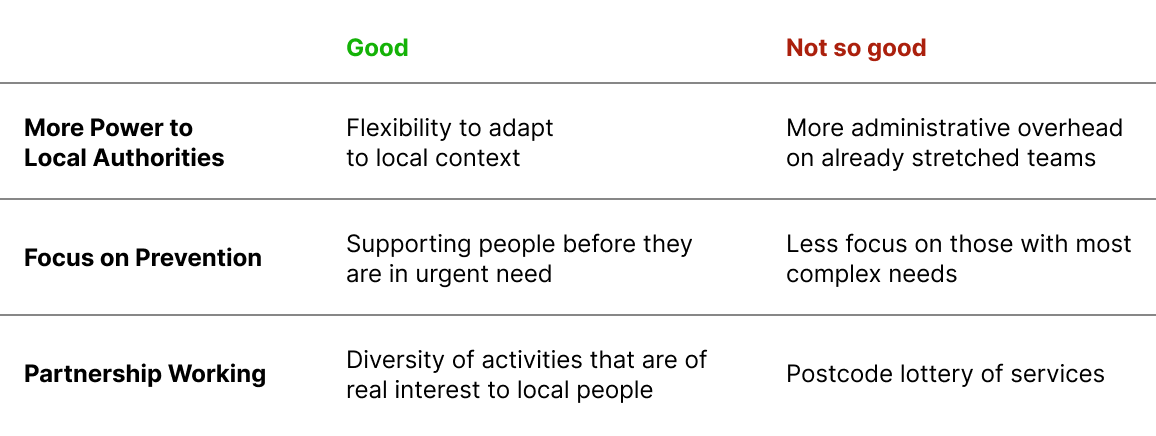

In our experience (working directly with 2 HAF programmes, over 100 providers involved in HAF, and speaking to many other HAF coordinators), we see 3 main benefits to the way HAF was structured:

These are our own opinions, though they are obviously shared by at least some people we have worked with.

All Power to the Councils

From the start, Local Authorities were given real power and real authority to manage their own provision. The Department for Education guidance mentions “flexibility” 14 times, and has a whole section on “tailoring provision”. This means Local Authorities can adapt to their local areas, fit the HAF programme within their existing programmes for young people, or public health & cost of living programmes. They can also choose their own providers (typically a mix of schools, charities, social enterprises or in-house provision), advertise and brand their provision in a way that makes sense and target particular communities or areas.

This is in stark contrast to other programmes funded by Central Government. As a clear and direct comparison, take the National Citizen Service, which is delivered by an arms-length Government body (the NCS Trust). Its branding, standards, providers and type of service delivered are all set and decided centrally. This often means services are delivered by much larger, less locally-focused organisations. As such, Local Authorities have very little power to shape provision to meet the particular needs and interests of their local communities. Or, take the Towns Fund, where Local Authorities had to jump through multiple hoops to justify the benefits of particular projects to be considered for funding at all by Central Government.

In general, the UK Government has been increasingly centralised over the past 10 years:

https://www.tomforth.co.uk/whylocal/

HAF is a clear exception to this broad trend.

Even more uncommonly, Central Government also allotted up to 10% of the funding to Local Authorities to spend directly on the management and administration of the programme, something that’s often lacking from similar funds. This has allowed Local Authorities to much more effectively take advantage of this opportunity.

Focus on prevention

Government interventions are usually directed to those who present with the most urgent needs, whether that’s in hospital A&E departments, or in children’s safeguarding. It clearly is the Government’s role to support the most immediately vulnerable people, but this can mean there is an underinvestment into preventative support — working with people before they enter into crisis or a position of urgent need. This is very commonly discussed (especially within Public Health), but actual examples of preventative programmes are less common. HAF is a clear example of Government actually working in a more preventative way.

23.8% of all pupils are eligible for Free School Meals. This is a much higher proportion than the 3.34% of Children in Need that are typically the focus of Children and Young People’s teams in Local Authorities. There are also often places available to non-eligible children on a paid-for or discounted basis. This means HAF works with families that are much less involved with existing local provision and support, and enables Councils and local VCS organisations to reach these children more proactively.

The flexibility from the DfE has also allowed Local Authorities to decide which department would be most relevant to manage their HAF programme, and thanks to the expansion of offering, it’s not always located within Children’s Services. In a brief survey of 32 HAF programmes (mostly from their job descriptions), we found 7 different departmental places: Children & Young People, Public Health, Neighbourhoods/Communities, Participation, Education & Schools, Physical Activity Teams and then some that outsourced management to the local voluntary sector or active partnerships.

HAF Programme Locations

In general, HAF doesn’t fit nicely into one of the departments. It is clearly cross-cutting and its success is dependent on collaboration and the sharing of expertise between different teams within a Council. It shows a much more holistic, and much less siloed approach to local service delivery that is typical of more preventative work.

Partnership working

As well as partnership within Councils, the HAF programme is clearly dependent on the existence and partnership with local organisations: both voluntary, private sector and schools.

This means that provision can be incredibly varied and matched to the needs and interests of local children. Local Authorities can take an asset-based approach, to encourage and build upon existing strengths in a local area. That might mean sports, arts, culture, gaming, education or access to nature. The choice is made entirely by children and their parents/carers, and the voluntary nature of the provision means that’s there’s clear evidence of which sessions are the most popular. In particular, in evaluations of the programme, and in the HAF programmes we’ve been directly involved with, there seems to be a strong desire for children to access alternatives to the more traditional sporting opportunities.

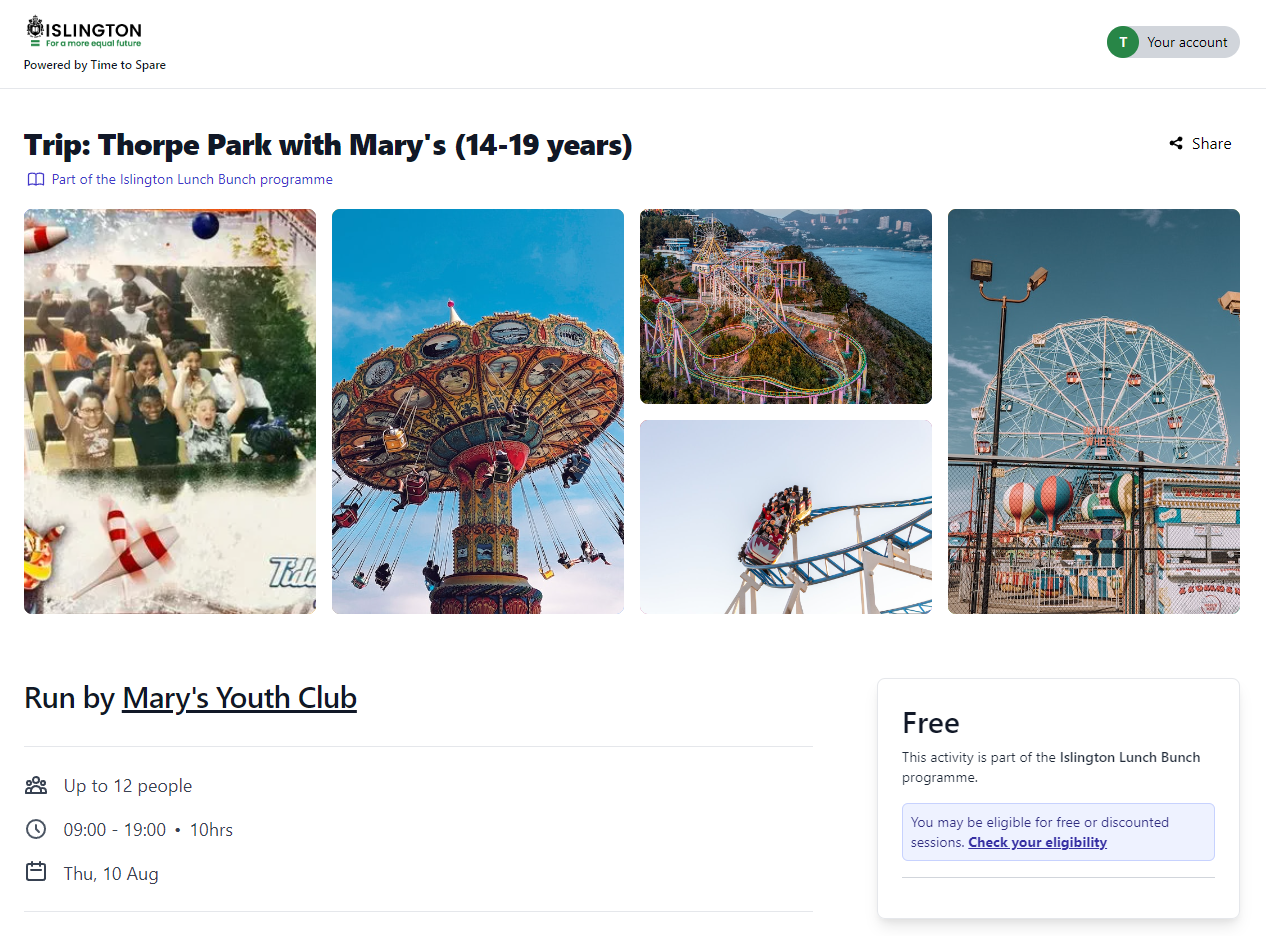

The outcome of this is some just really fun looking activities, whether that’s a trip to Thorpe Park

Special effects workshops:

Or re-enactments of the Matilda musical:

And it’s not just the direct service delivery that is working closely with local organisations. Part of the aims of the programme were to encourage more signposting and increase the awareness of other local support, e.g. food banks, Citizens Advice or other community organisations.

Crucially in all of this, HAF is quite rare in allowing funding to be used to support and build upon existing local infrastructure. It’s not a top-down fund that encourages national organisations to sweep in and start from scratch. It instead allows Local Councils to provide additional funding to local charities and social enterprises, and to use this funding to better connect together organisations, whether that’s in local food partnerships or other networks.

Growing pains

But there is a dark side.

Each of these benefits have a clear trade-off, and cause very real problems.

- More power to Local Authorities also means more responsibility, more accountability and ultimately more administrative burden on already stretched teams. Especially when the roll-out was so frantic, and when there was so much encouragement to work with smaller, local organisations.

- Working with a larger group of children also means that support is less focused on those with the most complex needs, for example those with SEND (Special educational needs and disability) or with EHCPs (Education, Health and Care Plans). Especially when there was no extra funding for these individuals.

- Working and depending on partnerships with local organisations also means there is a natural postcode lottery. Even with central minimum standards, there will be areas with fewer options, and activities that are better organised than others.

To add to our previous table:

Administrative cost

As a result of the compressed implementation timeline, the muddy and changing guidance from the DfE, and because of the complexity of working with so many different partners (schools, VCS organisations etc), HAF has been a struggle for Local Authorities to manage. The fact that the programme happens while other Council staff are more likely to be away also doesn’t help.

This is complicated further by the nature of the provision and providers. They are typically smaller, less frequently involved in commissioning processes, and there are simply more of them than for many other programmes. Many providers are not able to offer the whole 4 weeks of a summer programme, or offer 4 hours per day, so some areas have encouraged children to “pick and mix” between different locations and activities. This makes it more difficult for parents build a timetable of activities, and causes issues with potential double bookings or confusion around which sessions their children are eligible for.

Despite all this variation, Local Authorities still need to ensure a certain minimum quality level of provision of both the activity, with respect to safeguarding, SEND provision etc, but also regarding the food provision. For provision offered outside schools, or where school kitchens are closed over the holidays, this often means working with external caterers, which is yet another relationship that needs to be managed. It also means local organisations and Local Authorities need familiarity with food safety regulations, awareness of allergies (especially with Natasha’s Law) and cultural food requirements.

Another key issue is that while the programme delivery is decentralised to these local organisations, its management and reporting must be done centrally. The DfE asks for reporting, both in the form of quite comprehensive attendance statistics, but also in more qualitative detail, for example this report from Enfield. Local Authorities also need to collect information about attendances and session availability so they can better plan and prioritise services for the next programme, and advertise and adapt the current programme.

Collecting centralised and standardised statistics from disparate sources is the classic administration challenge. It is made even more difficult by the multiple-level reporting structure of the HAF programme. The data must flow up from individual youth workers, to provider administrators, to HAF coordinators, to the overall Local Authority HAF report and ultimately to the DfE. At each stage, every individual involved has to battle with different document types (PDFs, Excels, Word Documents etc), and different ways of collecting this same data.

It’s no surprise it can get chaotic.

Questions of eligibility

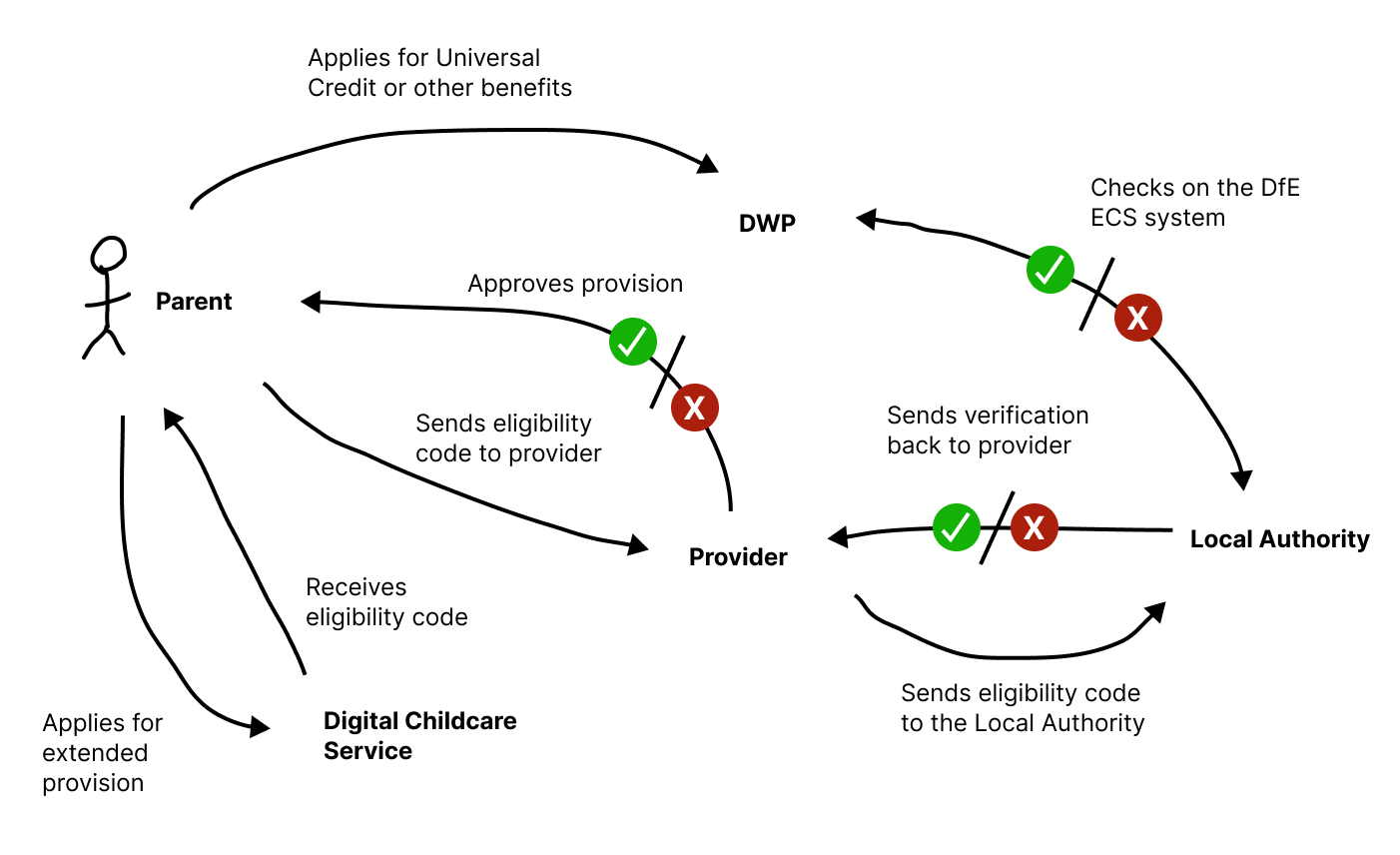

There’s a famous “law” in software: Conway’s Law. It states that a piece of software will follow the contours of the org chart that made it. Similarly, Government service delivery often follows the boundaries of databases of people held in different departments. That’s why the GP surgeries always want your NHS number, but the DWP want to know your national insurance, and the DVLA your licence number. Every database has its own system of telling people apart.

The problem with HAF is that the database for determining eligibility (whether someone is on benefits-related Free School Meals/FSM), is not collected or maintained directly by the people delivering the service (Local Authorities or local VCS organisations). FSM eligibility is determined by whether parents are recipients of Universal Credit, Income Support, or a number of other benefits, managed by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). This information is then shared with the Department for Education.

Local Authorities can only access this information for specific purposes through the Department for Education’s Eligibility Checking Service. They need to agree that they will use this information for checking whether someone is “eligible for funded early years provision, free school lunches and, where provided, milk and for the verification of eligibility for 30 hours free childcare”. And this process is far from straightforward.

The process for checking the eligibility for 30 hours free childcare looks something like this:

Because this system is so convoluted, and doesn’t work as a direct comparison for HAF as there is no central “Digital HAF eligibility service”, different areas have come up with their own ways of checking eligibility. Whether that involve pre-registration, codes shared by schools, fuzzy matching to other datasets or simply using a trust-based system, none of them are perfect and all of them impose significant administrative costs to parents, Council staff, school staff or provider staff (or all 4).

SEND provision

A big problem with the way that the HAF programme is focused on a larger number of children, is that it may not focus as much on children with the more complex needs, especially those with SEND and EHCPs. Some providers of HAF programmes are often not able or prepared to offer the kind of intensive 1-to-1 support that some children need. This is especially true as there is no incremental funding for children requiring 1-to-1 support available from the DfE — just an allowance that up to 15% of attendees can be non-eligible for benefits-related FSM.

The DfE guidance asks providers with a bespoke offer for children with SEND to clearly highlight this, however there may be a number of providers not offering bespoke programmes who can nevertheless accommodate children with certain needs and requirements. This can make it very difficult for Councils to understand the level of SEND provision that is actually available, and also where to find further provision when there may be no extra budget to pay for more staff or more training for providers.

This is particular difficult for Councils, as those with SEND will likely be a large proportion of the children wanting to attend. This is partly because this is the group that has the most frequent contact with existing Council programmes and staff in Children’s and Young People’s teams, so they are more likely to be aware of and engaged with the available provision. This is similar to our previous discussion around the Cost of Living crisis and the need to “Search outside the Council Streetlight”.

Local partnership working:

While it’s great that HAF programmes work “through” existing local organisations, this raises the obvious question: “what if there is no local provision?”. Or, what if the existing local provision is unbalanced, or not very suitable for the needs of local children?

Between 2010 and 2019, youth services spending in England and Wales has been cut by 71%, or £959 million per year. A new £200 million fund for HAF is obviously welcome, but comes nowhere close to replacing the services that were previously available. Moreover, this meant that is some regions, when commissioners went looking for the “local providers” suggested by this new model, there weren’t enough to find.

As one evaluation from the North East found: “There just isn't a mature market of youth provision in [name of region] because it's still kept in house in the council so there isn't an army of VCS organizations that aimed at providing youth services in [name of region] because it's in house”

The end result of this is a clear postcode lottery of services. In some areas, with historically well funded voluntary sector provision, there may be more opportunities and better services. This is true between different Local Authority Areas, and even within them.

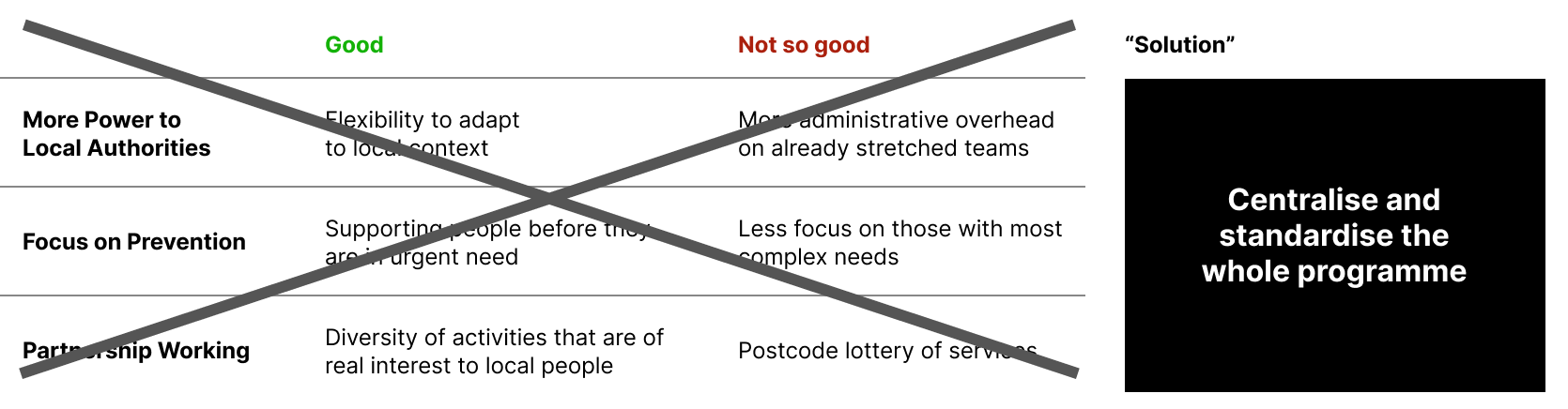

Throwing the baby out with the bathwater (don’t do that)

Our worry is that these problems are readily apparently and immediately painful. Worse still, these problems become more and more obvious the better a Local Authority manages the programme. In a well managed programme, where the Council has a true overview of what’s happening on the ground, they’re actually more likely to notice the gaps in provision, the variation in the service provided and are likely to spend more resources managing this. So it seems very tempting to try and remove these problems.

Typically, the way Government removes problems of variation is to increase standardisation and centralisation. But this would remove a lot of what makes the programme work. It’s a bit like sanding off all the knobbly bits of a jigsaw piece. Sure, it makes it more consistent, but it also kind of defeats the point:

This especially concerns Central Government. Whitehall is far enough away from the end-delivery of the programme that you may not see the extent of the benefits of a more tailored and decentralised service, but probably close enough to still hear issues with particular types of provision. It’s easy to be convinced that reducing the number of providers and increasing the minimum standards of provision would reduce the risk involved, and would reduce the likelihood of an individual activity going badly.

But, as in contracts all over Central Government, this would be a mistake. It would return HAF to the norm, a situation where large national providers can be more concerned with ticking boxes and meeting standards than actually delivering the best possible service, as has been identified in employment programmes, work-based learning, and in adult social care.

New models need new environments

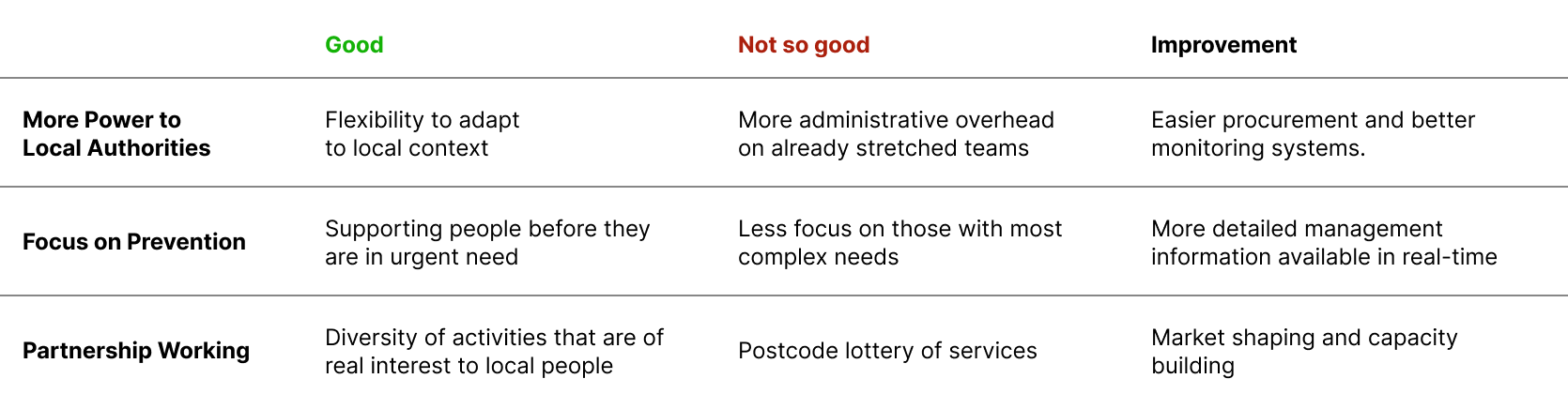

Instead, we should look for specific ways of improving the problems caused by this new model:

Computer says yes

For example, instead of adapting the programme to better fit the standard administrative procedures of Government, maybe the systems need to be changed to better fit the realities of working with smaller organisations.

It’s no secret that Government procurement processes are unpleasant. Even once you’ve gone through the formal contracting, tendering and diligence requirements, just receiving money from Councils can be like drawing blood from a stone. It’s a process designed for large Council-wide contracts with major suppliers, not smaller local organisations. The same issues that prevent SMEs from contracting with Government also make it much harder for local charities and social enterprises to be part of a commissioning process. In our view, where possible, Councils should instead take more guidance from their grantmaking processes — making it much easier for small organisations to access funding.

Likewise, as we have previously discussed, a better monitoring process is needed. When working with one or two large providers, it’s feasible to use a process of regular conversations and emailing poorly formatted spreadsheets back and forth. When you’re working with 20 small organisations, it isn’t. The pain of the monitoring process scales with the number of providers, not the amount of money spent. It becomes much more important to invest in improvements to this process, and embracing new technology to be able to properly monitor and manage all these different relationships and contracts. Whether that’s by implementing a central booking system to collect together all this data, or by allowing providers to collect information through registers and drop-ins, this process is more important for HAF than for many other programmes.

Government like SimCity

There also needs to be better access to management information, at all levels. Providers need information about how their activities are faring compared to others. Local Councils need to be able to see gaps in their provision, whether that’s by area or by population (e.g. age or SEND status). To do this, people also need access to more detailed information about children and parents. This needs to be available in real-time so that people have time to react and change the situation.

To fully enable this, we would suggest 2 changes to be made at a Central Government level:

- If the eligibility requirement is going to be strictly those on benefits-related Free School Meals, there needs to be a clear understanding at the national level that this needs to be in some way shared with Councils and providers, so they can sufficiently manage access to their programme.

- Secondly, the DfE should not be the “Data Controller” as specified in the Grant Determination letter. Instead, they should change the term to become the Joint Controller with Local Authorities. This would give Local Authorities more flexibility to collect personal information relevant to their own programmes, and to better integrate HAF provision into their other term-time work.

If these points were changed (or clarified), and if we gave Local Authorities and providers access to real-time detailed information about services, things could get quite exciting.

Opportunities for the future of HAF:

At Local Authorities, we could start to ask questions like:

- Is HAF providing a pathway into other local services? Is the signposting for other support actually working? Which of these pathways are most and least effective? How do we encourage them?

- Which groups of people are accessing HAF that aren’t accessing our other support?

- Which people did we expect to attend HAF, but haven’t? Why is that, and is there anything we can do to adapt?

- Which people return to HAF each holiday? How does this vary from the people that attend once and then not again?

- Is attending HAF impacting long term outcomes of child development or education?

- Does it have positive impacts on youth offending rates or employment opportunities later in life?

Similar questions could be also be answered for every single provider, so they could understand how providing HAF spaces affects their own individual goals (as charities, schools or social enterprises).

Even better, we could do this as it happened, without the need for an expensive evaluation project that’s destined to be always looking in the rear-view mirror. We can track intermediate outcomes in real-time even as we wait for the long term effects to become apparent.

It may sound a bit reminiscent of Dominic Cummings’ “Government by Dashboard”, but if we can make this readily accessible to teams in Local Government and local organisations, like you would for a computer game, it would give people real feedback to improve the effectiveness of HAF and their other programmes.

Market Shaping & Capacity Building

However, while dashboards can be quite interesting, the success of a decentralised programme ultimately depends on the providers actually delivering the service. If these don’t exist, don’t want to engage, or aren’t able to meet minimum standards for commissioning, the programme will be incredibly difficult to deliver.

To remedy this, HAF coordinators at Local Authorities should look to their colleagues in Adult Social Care for advice on “Market Shaping”. This already happens informally: HAF coordinators help facilitate the deliveries of food from external caterers, help with access to venues and provide extra funding for the administration of services. More clarity from Central Government about the likely continuation of HAF funding past 2025 would allow Local Government to invest more in this process. Likewise, if other programmes were run through the local VCS sector in a similar way, this market shaping would be easier — as contracting would happen more frequently.

A large part of this process would fall under the more general “capacity-building” umbrella, and in many places would fall under the remit of the local CVS (Council for Voluntary Services). These organisations can often offer support to local groups to become “commissioning ready”, helping those groups to set up the kinds of safeguarding, monitoring and evaluation needed to apply for and work on Government contracts.

The story so far:

At a national level, HAF is clearly quite a new programme, but from the conversations we have had with HAF coordinators, these changes are already moving rapidly in many places. Though it doesn’t seem like anyone has completely “cracked it”, these are clearly the directions many Local Authorities are moving in (and something we at Time to Spare can definitely help with — though we have definitely not yet “cracked it” either.)

What can the rest of Government copy?

The reason we’re so excited about HAF (and why we’ve just written 3,000+ words about it), is not just because of the trips to Thorpe Park. It’s clear to us that this model could be replicated across other parts of Government, with potentially great success.

We think it’s worth asking the question to Central and Local Government — what does a HAF-style programme look like for other service areas?

Adult Social Care

This is quite topical, given the announcement of the new £600m in extra funding to Local Authorities for Adult Social Care. This already took a similar approach to empowering Local Authorities — funding through existing channels and not requiring specific funding bids to Central Government. Though, there are still substantially more requirements as a result of the Care Act than exist for HAF.

But it might be interesting to think about what this could look like if it were targeting a larger group of people, with more of a preventative approach. There are ~400,000 Children in Need nationally, and there are ~840,000 adults receiving long term care support from Local Authorities. Is there an equivalent eligibility criteria to Free School Meal eligibility for older adults, that would be similarly a 5-10x larger number of people? Something that would reach a group of the population before they needed the kind of intensive support that Local Authorities often provide, perhaps even before receiving a care assessment?

And would it be possible to deliver this funding through existing charities and through existing infrastructure? There are many lunch clubs, community centres and exercise classes available in the community. Could these be better supported by a HAF-style national Adult Social Care fund to try and solve issues on a wider scale but at a lower level of need?

Elsewhere

It feels like there are other places across Government that would benefit from a similar approach, and other places where new programmes seem to be drifting in this direction already. Whether that is innovation funds in short breaks provision for children with disabilities, or preventative programmes for Youth Offending Teams, this is clearly a way of working that is becoming more popular with new initiatives. People designing and delivering these programmes should take notice of what happened with HAF, both the benefits and the problems that it caused.

About Plinth:

At Plinth, it’s our mission to enable this kind of commissioning model. Like many others, we believe that local VCS organisations often provide the most effective services and interventions. However, it’s not good enough to just believe it. In order to demonstrate this and enable it further, we need to help Councils, charities and social enterprises better solve some of the problems around management, reporting and analysis.

That’s what our platform has been doing for HAF programmes and in our other work with Local Government. If you would like to discuss more, please contact tom@plinth.org.uk