Philanthropy’s Identity Crisis: Talking VC, Acting Procurement

In strategy sessions and on websites for foundations and philanthropists across the globe, you'll increasingly hear the language of Venture Capital investing. "Catalytic funding." "First-mover advantage." "Disruptive innovation." This isn't coincidence — it's a deliberate shift as philanthropy increasingly models itself after Silicon Valley's investment approach.

It's easy to understand why. The Venture Capital model has created unprecedented wealth, has its alumni in the top positions of Government, and the sector is perceived as attractive and glamorous (or at least as much as you can be in a Patagonia vest). If philanthropy aims to solve intractable social problems, shouldn't it adopt the methods of the most successful problem-solvers in the private sector?

Yet, this borrowing of vocabulary and mindset comes with an unexamined assumption — that the fundamental dynamics of investing and philanthropy are similar enough to warrant the same approach.

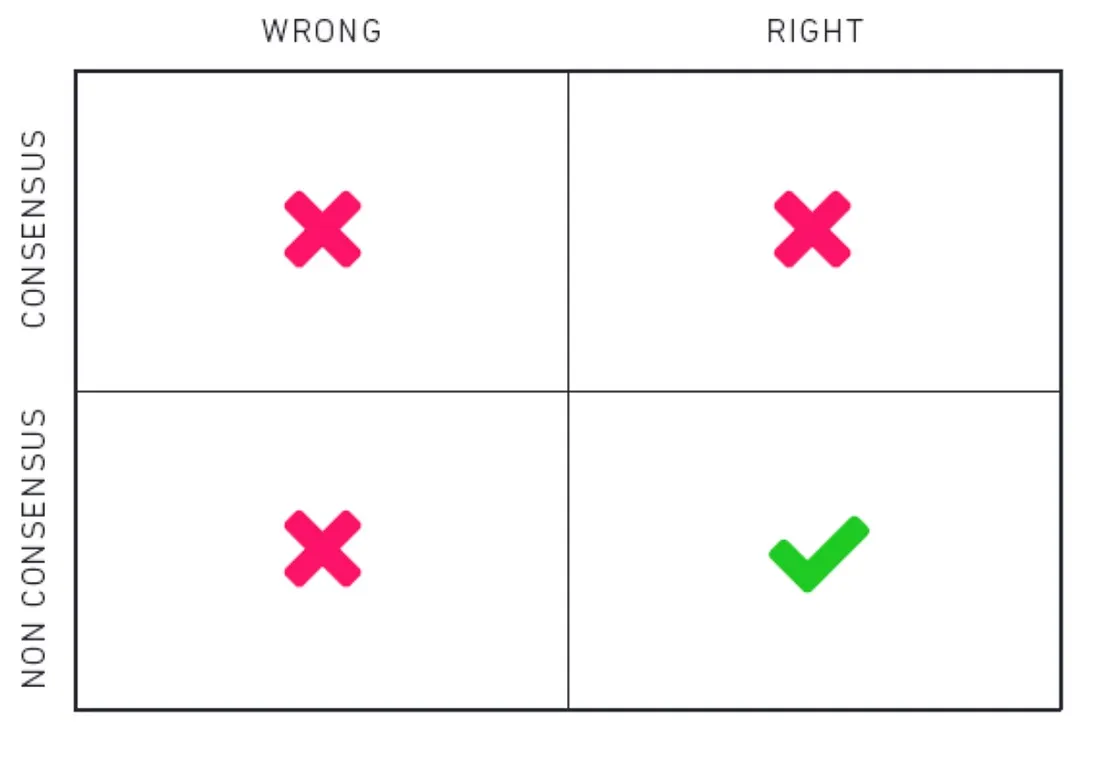

One of the core concepts in investing (particularly VC) is that you have to be contrarian and right. In philanthropy, you don’t. You just have to be right.

That changes everything about how we should think about funding innovation and risk.

In investing, returns diminish once others see the same opportunity. If you invested in Uber in its first funding round, you’d have made 5,000 times your money, if you invested a year ago, you’d have lost 2.5%. The only way to be a “good investor”, is to buy things (companies, commodities, currencies, etc), that are going to be more valuable than everyone else thinks, before everyone else realises.

This perspective on the world is deeply burned into everyone that’s ever worked in investing. Traders talk about “alpha”, VCs talk about “picking winners”, and hedge funds boast about their "proprietary insights”. In investing, if you don’t have an edge, you’re nothing.

However, philanthropy is not investing.

The crucial missing ingredient is ownership of the return.

An investment buys you a slice of future returns — a share of the pie. But once those returns become obvious, capital floods in, and the opportunity gets competed away. That’s what drives diminishing returns and why investors are always hunting for an edge: the moment something works, it stops working.

In philanthropy, this doesn’t exist. Your donation or your grant gives you no share of the non-profit, no claim to the “social benefit” generated by their work — ownership still fully sits with the mission, and society as a whole. That’s why it’s charity — obviously.

You don’t need to “get in early”, and actually often it’s a better strategy to back a programme or an organisation once it’s been proven to work. It’s often cheaper and lower risk to fund, with none of the downsides you’d get if you were an investor — because the opportunities to make an impact are not ever going to be competed away.

We shouldn’t think about most philanthropy as investing. A better analogy is procurement.

Philanthropy as procurement

Yes, it’s a bit of a step-down the excitement rankings — from helping “the daring build legendary companies” to “no one ever got fired for buying IBM” — but let’s elaborate.

For many charities or non-profits, even large grants are not really used as capital to invest in new programmes or try new things. Instead, they’re treated as revenue to spend on mundane things, like rent, staff salaries, heating bills or tax. In essence, grants and donations are buying outcomes or impact, often in an extremely tangible way.

Everyone knows what a youth club does. Everyone knows why a food bank needs to exist. Everyone knows how a malaria net works. Donations or grants trade money for more youth clubs, more food banks or fewer kids dying from malaria. Most philanthropy should be focused on making this trade as effective, as efficient and as large as possible.

And this isn’t easy. Being a procurement officer may not be glamorous (apologies to the many we work with…), but it is still very important. Crucially, it’s a weak-link problem — the big mistakes matter more than the big successes. Funding a youth club with inadequate safeguarding will lead to much more harm than good, just as poorly distributing funds in an emergency can lead to a “second disaster”. In these kinds of cases, there’s both direct harms to the people involved, and other indirect reputational risks to the people who were part of funding it.

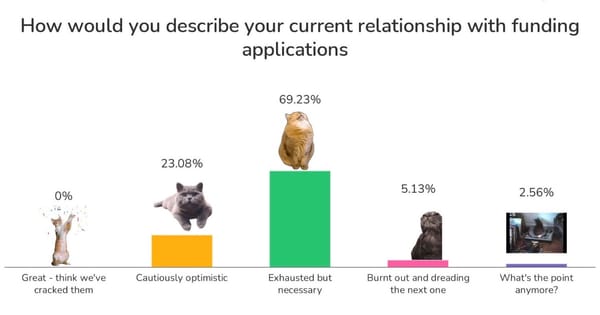

Which is why, despite much of the external communication from large grant-makers being about “innovation” and “supporting bolder change”, most of the internal operations are actually about minimising risk. Most of the people involved are spending time running due-diligence checks on organisations, making sure projects match their legal requirements, and considering whether there would be reputational concerns with particular individuals.

This all actually makes complete sense if philanthropy is acting more like procurement than investing. Funders don’t need to be first movers, they just need to be smart buyers.

Doing procurement more effectively

The problem is that funders are talking the investor talk, but walking the procurement walk — and the conflicts between the two are responsible for many of the problems with grant-making.

The investor mindset resists exactly what makes procurement effective: investors avoid reinvesting when others have caught up, they prioritise flexibility over efficient process, they keep criteria deliberately vague to discover contrarian outliers, they constantly shift strategies to find new opportunities and they idealise innovation even when incremental improvement delivers better results.

But if funders can choose to shake off the burden of trying to be “investors”, there’s an awful lot they can do to become smarter buyers:

- Renew and expand contracts after the first grant — if many charities deliver similar work, and the main risk is funding an inappropriate organisation, funders should be giving more repeat grants. You’ve already done the due-diligence heavy-lifting, and you have all the additional insight from their monitoring and reporting. If the first grant went well, a “regrant” should be a common, perhaps even the default, scenario. Rules like “don’t reapply if you’ve received a grant in the past X years” are particularly counterproductive.

- Invest in process automation — if the job is to purchase outcomes and impact in the community, you should be trying to cut out all of the unnecessary costs and inefficiencies from this process. Maybe this looks like the “Lean Review” done by foundations like Northern Ireland Community Foundation’s, or perhaps that’s investing in Plinth’s AI tools to support with automating due-diligence and eligibility checks (shameless plug).

- Make it clearer what you’ll fund — no procurement process starts out with open, all-encompassing criteria. It would lead to an unmanageable influx of enquiries from every potential supplier under the sun. Yet, this is common practice in grant-making, and is one of the contributors to extremely competitive processes for applicants, and mounting administrative costs for funders. Funders should be much more specific about what they want to fund.

- Keep consistent strategies — if you relieve yourself of the pressure to find the “neglected” problem, or to “lead the change” in a space, because there are so many things that you know work that require continued funding, you don’t have to keep changing your strategy. That in turn means charities you might want to work with have a clearer understanding of what funders do and whether they will be a good fit.

- Stop encouraging core work to be dressed up as innovation — finally, if funders can stop pretending to be investors, they can openly support charities’ essential, core activities rather than pressuring them to disguise them as novel ideas. Both sides can be more comfortable with the honest reality that most of the time, grant funding goes to fund the continuation of existing work.

Good procurement is hard, as is evidenced by how difficult it is to work with so many procurement departments. Just using the word procurement might be enough to bring some charities out in cold sweats from painful past experiences, but unlike rigid government procurement with its inflexible RFPs and opaque decision-making, philanthropic procurement could be more adaptive and relational.

The best funders can combine clear criteria and consistent processes with the flexibility to back promising organisations for multiple cycles, adjust reporting requirements based on grantee capacity, and make thoughtful exceptions when the situation demands it. It doesn’t need the “investment” façade to do this.

Do procurement well, not investment poorly.

The exceptional cases

Of course, there are situations where funders should act like investors, both in promise and in practice. An entirely standardised procurement-like approach would likely lead to stagnation across the sector pretty quickly.

For problems where there’s no proven solution, someone has to fund things that are a bit more out of the box. Right now, by using the wording of investment, but the practice models of procurement, funders are failing these areas too, perhaps even more-so than elsewhere.

While most charitable funds should lean into their procurement-like reality, a small, dedicated portion should be explicitly earmarked as “risky investment”.

This portion should only fund things that are explicitly contrarian and at high risk of failure. “Risky” might mean new untested approaches or technology, things that need patient long-term thinking, areas that are currently extremely taboo, or radically different ways or making decisions and sharing power. But importantly, this should be a clear and obvious different mode of thinking to normal grant-making, and in practice would probably need to be run as a separate fund, or by different people.

Because in the right contexts, this genuinely contrarian approach can have really important effects, but where the scale and direction of impact may not yet be clear, as the real-world examples clearly show:

Funding untested approaches:

- Direct cash transfers: GiveDirectly's universal basic income trials in Kenya challenged conventional wisdom about aid effectiveness

- Digital innovation: National Lottery Community Fund's Digital Fund supported tech solutions where outcomes were unproven

- Medical breakthroughs: Early funding for malaria vaccine research that traditional healthcare investors considered too risky

- Housing innovation: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation's backing of "Housing First" when conventional wisdom prioritised treatment before housing

Tackling unpopular or taboo issues:

- Marginalised communities: Open Society Foundations' funding of sex worker advocacy when few would support such work

- Reproductive health: Hewlett and Packard Foundations' sustained funding for abortion access despite political controversy

- Mental health alternatives: Beckley Foundation, MAPS, and Wellcome Trust's pioneering research into psychedelic therapy despite legal obstacles

- Environmental activism: Sea Shepherd's direct-action conservation work that more mainstream funders avoided

Taking the long view:

- Existential risks: Open Philanthropy's work on AI safety and biological threats requiring decades-long thinking

- Nuclear security: MacArthur Fund's commitment to nuclear threat reduction over generational timeframes

- Climate intervention: Harvard's Solar Geoengineering Research Program exploring controversial but potentially necessary approaches

- Ecosystem restoration: Arcadia Fund's rewilding initiatives requiring patience beyond typical funding cycles

- Early childhood development: The decades-long Perry Preschool Project that transformed understanding of early intervention benefits, funded continually by HighScope Educational Research

When early "investor-style" philanthropy successfully proves a risky approach works and is important, what should happen next is clear: "procurement-style" funders ought to step in, providing sustained funding to continue or scale these proven interventions. This creates a healthy ecosystem where risky innovations that succeed can find long-term support.

However, in practice, this handoff rarely occurs because all philanthropic funders face strong institutional pressures to minimise risk. Unlike VCs who can tolerate frequent failures, and take almost perverse pride in them, because their few successes generate enormous financial returns covering all losses, philanthropic funders gain no direct financial benefit from their successful bets. Without this offsetting reward mechanism, the natural tendency is to drift toward safer, more conventional approaches — even for funds supposedly dedicated to innovation.

The challenge for philanthropy, is to create new incentive structures that genuinely enable and reward risk-taking. We need better offsetting mechanisms to recognise the significant social value created when funders’ risky bets succeed. Until we solve this incentive problem, philanthropic organisations will continue using venture capital language while avoiding the actual risk-taking that makes the VC model effective.

Overall

The irony is that by playing at being investors but practicing as procurement officers, funders are getting the worst of both worlds — the stresses of aiming for innovation without the real risk tolerance, and the constraints of procurement without its discipline and efficiency.

For philanthropy to reach its full potential, foundations must be honest about which mode they're operating in. The vast majority should embrace their role as professional buyers of social impact, bringing the appropriate toolkit and mentality to bear on maximising their effectiveness.

And for those looking to encourage the true risk-capital approach, we have a suitably contrarian suggestion next time.