The Messy Middle: What UK Community Foundations Can Teach America

You might be well-endowed, but it’s what you do with it that matters.

My main takeaways from the CoF conference in Minneapolis last week were not what I anticipated.

American Community Foundations are sitting on huge piles of money, but could be doing a lot more with how they give it out. In a lot of ways, and unexpectedly, they are seriously behind the curve.

Frankly, I found the difference between the US and the UK confusing, and spent most of my time asking pesky questions.

From this outsider’s perspective, these issues feels downstream of the incentives set up by tax policy, donors and the foundations themselves.

Here’s what I mean:

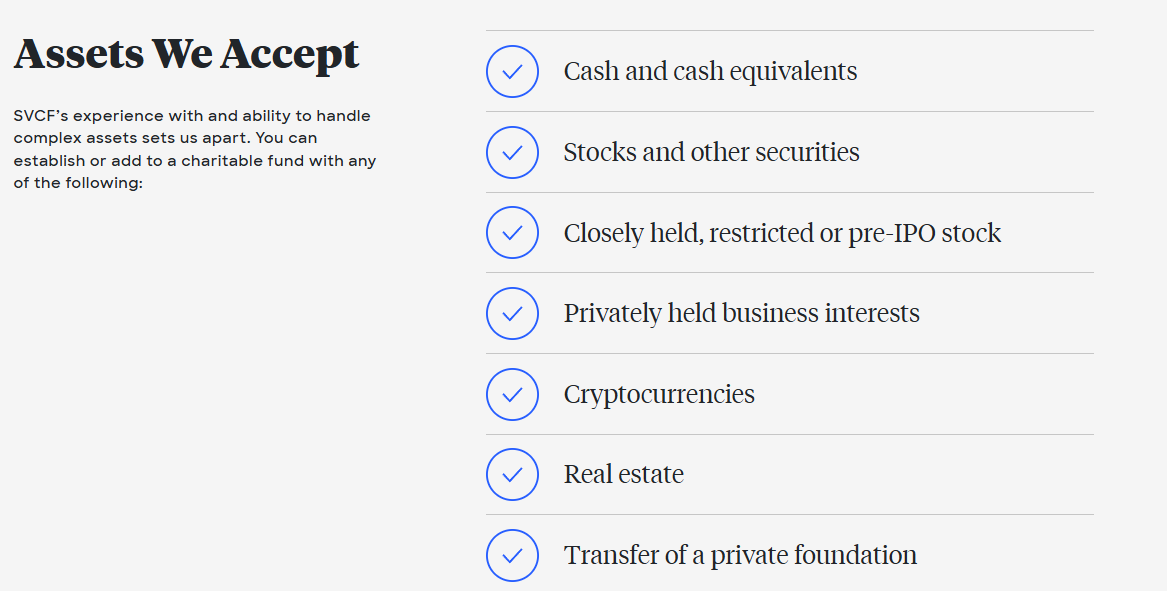

Asset Management

When we met someone from a Community Foundation, we usually heard 2 things:

- Where they’re from

- How many millions or billions of $s they manage

That is how size is measured.

The explicit focus is on accumulation, not distribution. People at foundations who know their exact asset values can struggle to describe which non-profits they've made grants to.

And if you go to their websites, you’ll see different asset-management strategies, different asset types they can handle (stock, crypto, property etc), and their fees: charged as a % of assets under management.

Community Foundations will even offer their asset management services out to local non-profits, offering to manage/acquire their own endowments/reserves.

Crucially, you’ll also see their tax advantages…

Tax Incentives

The structure of philanthropy in the US depends on specific rules made by the IRS (US version of HMRC). Donors can deduct charitable giving from taxable income, but there's a catch - donate over a certain amount (~$20,000, it depends) and you need itemized receipts from every charity.

This bureaucratic nightmare means wealthy donors rarely give directly to charities, like they would in the UK.

Enter Donor Advised Funds (DAFs). Donors put money into a DAF, get their tax deduction immediately, only need to list a single charitable recipient (the DAF), and then tell the foundation where to distribute funds later.

They’re Donor Advised by name, but often Donor Directed in practice. The donor will typically tell the foundation (the DAF sponsor) exactly which charity they want to give to, how much, and when. Many DAFs will donate to a select few organisations, and often just 1, or even 0.

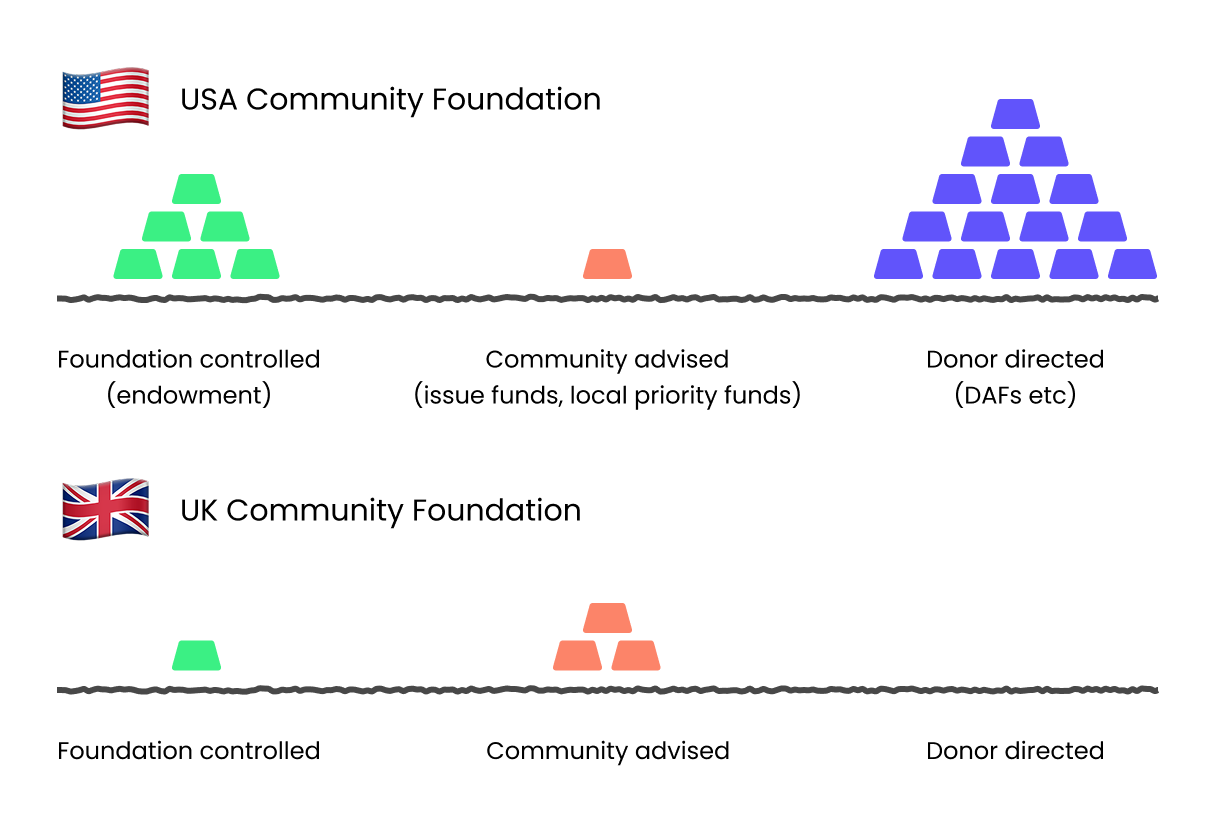

The Barbell

But Community Foundations also have their own endowments, often massive. Some of the largest manage over $5 billion with no donor restrictions, and the largest 100 all manage more than the biggest in the UK.

They distribute a % of these every year, and it’s entirely up to them how much, and where they donate it. It could be as low as 0.5% (if you’ve heard of a 5% rule - that only applies to private foundations, not community foundations).

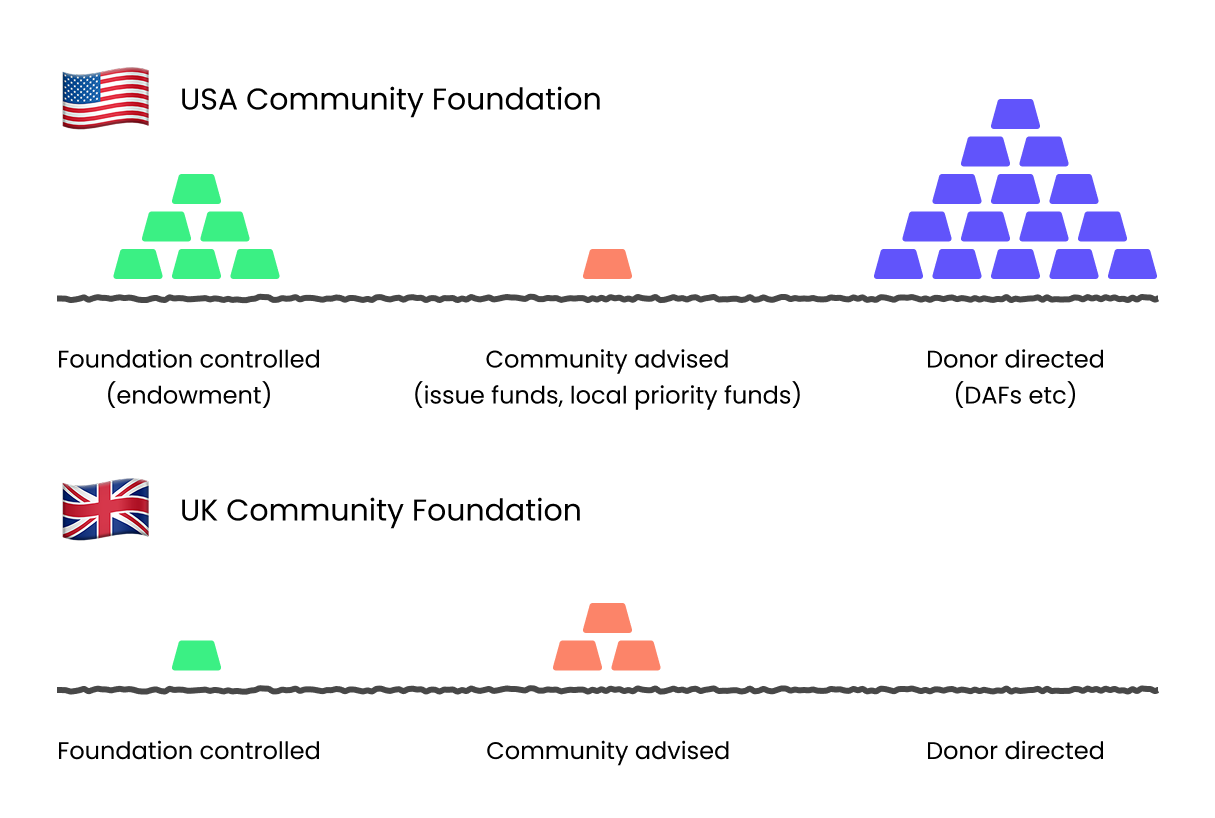

So they operate on extremes:

- On one end: Endowment funds where boards decide everything

- On the other: DAFs where donors call all the shots

- In the middle: Almost nothing

And that thin middle ground - issue-focused funds where foundations prepare open grant rounds and advise donors based on community needs - is where UK foundations excel and most of their grantmaking comes from.

It's the difference between a donor saying “give $10k to this youth club” vs the foundation saying “we've identified these 3 food banks serving populations with the highest need - here's why we recommend them”.

But in the US? The middle exists, but barely. DAFs are largely about compliance and payments infrastructure, meaning CFs face stiff competition from Fidelity, Schwab, and fintech start-ups like Daffy.

The value of the middle

This middle point, where the process is driven by the foundation, and approved by the donor, is tricky, in a good way. It requires the foundation to really know what is needed in a community, to have trusted relationships with community groups, and to really demonstrate the value of their expertise.

If they don’t, the donor (or often, Local Government funds) will just go somewhere else.

It forces CFs to do a good job.

And, when foundations get paid based on the amount of money they help disburse, not based on their assets they’ve accumulated, it pushes the CF’s incentives in the right direction for the community.

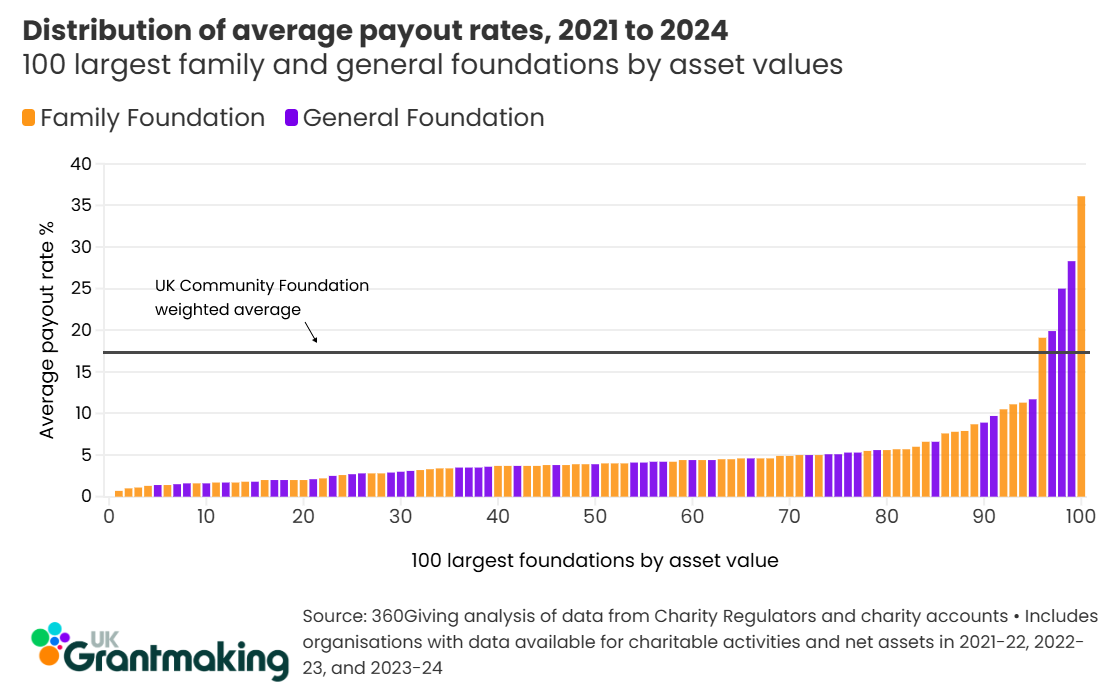

This shows in the numbers too - recent research into UK foundation payout rates (combined with some quick maths) reveals that Community Foundations are paying out around 3x as much as other foundations: 17% vs the ~5% average for the largest 100 foundations.

Right now, these incentives don’t exist in the US. And it shows.

The processes, the relationships and the systems clearly lag behind as a result.

The Processes & "Trust Based Philanthropy"

We heard a few conversations about being more Trust-Based. This is a sort of US equivalent to IVAR (the Institute for Voluntary Action Research)'s “Open and Trusting Grantmaking”: a campaign to improve the grantmaking processes of foundations.

But like American chocolate, it definitely doesn’t pack as much punch as the UK version.

There’s no equivalent of IVAR’s accountability/review cycle, and the recommendations are much less specific and tangible:

| Category | 🇺🇸 Trust Based Philanthropy | 🇬🇧 IVAR Open & Trusting |

|---|---|---|

| Core Practices |

6️⃣ practices: 💰 Multi-year unrestricted 📋 Do homework 📄 Streamline paperwork 💬 Be transparent 👂 Get feedback 🤝 Support beyond $ |

8️⃣ commitments: ⏰ Don't waste time ❓ Relevant questions ⚖️ Accept risk 🚀 Act urgently 📊 Be open 🔄 Be flexible 💬 Purposeful comms 📏 Be proportionate |

| Specificity |

📖 Broader principles 🎯 Values-based framework |

✅ Detailed commitments 📊 Measurable outcomes |

| Accountability |

🪞 Self-assessment 👥 Peer learning 🤲 Voluntary participation |

🔍 External review 📅 Every 2 years 💬 Charities assess funders |

| Timeline | 📅 Ended 2024 | 🏛️ Ongoing program |

| Data | 🤝 External research | 🔬 Primary research |

And that reflects the wider environment.

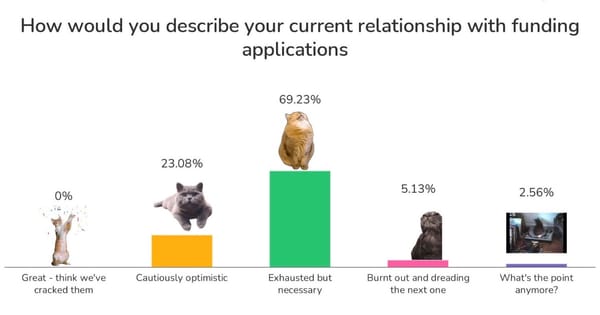

While we might complain a lot about problems with funder practice in the UK (and we have certainly done our fair share), Community Foundations in the US have grantmaking processes that are on the whole not as applicant-friendly, as transparent or frankly as helpful as the UK.

Some of the things done as standard in the UK, like having different length application forms for big vs small grants, were viewed as novel innovations in the US.

Invite-only grant rounds are the default, and clear guidance on funder priorities is not all that common.

There’s still generally something of an attitude of “non profits need to get to know us”, rather than “meeting non-profits where they are”. It's still donor-driven. There's not as much evidence of grantmaking processes being in service of the community.

Community Relationships

I think (though it’s hard to tell after a week), that this has sometimes led to more strained relationships with communities. Particularly in the case when foundations are administering Donor Advised Funds, as this can limit the transparency a foundation can give about their donors, income sources and grants.

At the conference, I heard of one CF that had actually been sued by their local community for not adequately delivering on their mission. Another Foundation talked about a participatory grantmaking discussion that got so heated, the community simply dropped out and refused the money.

Though of course, UK Community Foundations can also have fractious relationships with local community groups, we probably just sue each other a bit less (again, because of the incentives, but that's another issue).

At the conference, there was a clear aim to fix this where these relationships were difficult, with a lot of focus on “Community Listening”.

I especially enjoyed the session run by Community Heart & Soul about the work they've done in rural communities to help Community Foundations facilitate conversations about what communities really want and need in their local area. So I don't think it's just foreigners that can sense a problem, or identify solutions.

Processes & Systems

On technology, from the land of Silicon Valley, we definitely expected more.

But, given the different incentives (towards donors and assets, rather than on community-focused grantmaking), we probably shouldn’t have been surprised that systems were lacklustre.

There wasn’t much innovation in Grant Management Systems, and surprisingly barely any mention of AI, compared to the frequent discussion at the UKCF conference last year.

Certainly, there was no evidence of the number of experiments and new ideas happening in the UK (both from us here at Plinth and elsewhere), whether that's on applicant <-> matching, better impact reporting or on using AI to reduce the application burden.

The most engaged conversations I heard about software were around the benefits of adding character limits to application questions.

But then some things we’ve built in the UK, like our automated due-diligence checkers and assessment support just aren’t as relevant, as grant funds are so much less likely to be open/competitive. To be honest, I'm not sure whether it's processes stopping innovation in tech systems, or vice versa.

Bright spots

Despite these systemic issues, we encountered some genuinely impressive innovations that show what's possible when incentives do align with community impact.

And what I can say is, when Americans go, they go hard.

We came across:

- Foundations working in rural regions that could give out $1000s on the same day as the initial application.

- A foundation buying billboards advertising the results of their grant programmes, so the whole community could see the impact.

- A common decentralised platform for grant applications, backed by $100s of millions.

- A network of foundations raising over $5 billion in new money to be spent supporting communities in just a small city, after the George Floyd protests.

- A foundation suing the Federal Government for cutting its contracted grant programme to indigenous communities.

And I particularly liked the Minneapolis Foundation’s campaign to tell donors to:

Get off your assets

They're working against the incentives, and trying to double the amount that their donors actually spend each year, and to put the emphasis on actually getting funds moving in their community.

So when the focus is there, big things get done.

Learnings for the UK

UK Community Foundations are newer, so haven’t had time to build up these massive endowments that you have in America.

A large endowment sounds nice, but they clearly have their downsides.

The UK model creates an interesting tension: CFs need to prove their worth annually to keep funding flowing, which keeps them accountable and responsive. But this also means they're often dancing to the tune of whoever's paying - whether that's government with its electoral cycles or corporations with quarterly targets.

The sweet spot might be having enough reserves to think beyond the next government contract (maybe 2-3 years of operating costs?), but not so much that you become disconnected from community needs. Enough stability to make long term investments in the community, but not enough to get complacent.

Above all, UK foundations must resist the temptation to retreat from the messy middle. The moment donors stop questioning whether you're the expert in where their money should go, you've probably stopped earning that trust.

Of course the UK could do more to follow the best of America: releasing money for individual projects more quickly, building a wider donor base to support with things like match funding, and yes - having enough breathing room to think strategically.

But building massive perpetual endowments? That feels like solving the wrong problem.

Ideas for the US

But in truth, I saw much more that the US could learn from the UK.

And I have a few concrete suggestions:

- Create a mission-focused DAF that charges based only on distribution. As the foundation, you would then run an open process, produce research on your community, evaluate the impact and report back to donors who want to tackle a particular issue, but don’t know quite how.

- Check out IVAR. They don't normally work with non-UK foundations, but if you can fake a British accent, maybe you can get away with it. At the very least, steal and implement all their recommendations.

- Lean hard into the community listening work that I heard Community Heart & Soul talk about with rural foundations.

- Build the evidence case. Take the “Vital Signs” concept from Canada and tailor it for a US context, like in Flint, Michigan.

- Set up better tech systems to support those new processes (though we would say that).

And what most of these have in common: US foundations should look for ideas outside the US more often. It's telling that the UKCF conference was extremely international, with visitors from across Europe, Africa and Latin America, whereas I met no-one else last week who wasn't from North America.

With over 1,000 community foundations managing $100+ billion in assets, even small improvements in distribution efficiency could unlock billions more for communities that desperately need it. The question isn't whether American foundations can afford to innovate - it's whether they can afford not to.

And if anyone in the US, or the UK, wants to talk more about this difference, or get help with tech solutions to enable better grantmaking, let me know: tom@plinth.org.uk.