Using AI to fix grant-making

Why we think grant-making needs to improve, how we think our platform can support that, and why the model we’re offering enables it.

When we announced the no-win, no-fee model for AI grant writer tool last week, we did it all wrong.

Instead of explaining why we’re doing what we’re doing, we started by trying to pre-emptively address potential criticisms. It meant we were talking past people, and we had to get over 100 comments deep on multiple LinkedIn threads to really explain how it worked. Essentially, we failed comms 101.

This time, we’re going to start by explaining our positive model for change. We thought we’d spell out exactly why we think grant-making needs to improve, how we think our platform can support that, and why the model we’re offering enables it.

So we’re going to zoom out to the big picture, zoom in to an individual charity applying for an individual grant, and then zoom back out again, going through:

- What’s wrong with grant making?

- Why does a charity decide to apply to a grant?

- How do charities choose how to apply?

- How does our platform make that process more accessible?

- Why is a no upfront cost model important?

- How does a no upfront cost model impact the cost to all charities

- How does it impact the grant application process overall?

What’s wrong with grant-making?

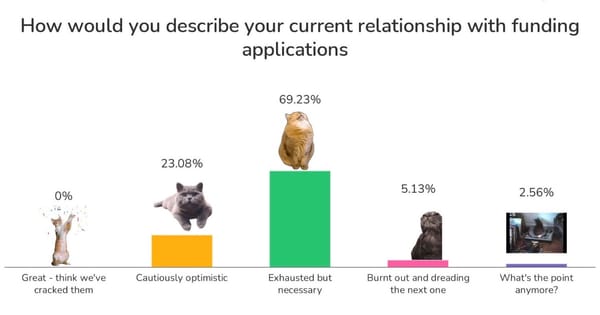

We wrote a piece 5 years ago about the cost of applying to grants. We assessed that 46% of grants cost more than they’re worth. After that, we spoke to Caroline Fiennes and Sarah Sandford at Giving Evidence as part of the fantastic report they wrote on the same problem.

That report conservatively estimated the cost of grant applications as “at least 5.6% of the amount raised, and at least 17.5% for small charities”.

And while the precision of the cost estimate is useful, it’s not qualitatively new information. This is a longstanding issue, with many attempted solutions. All of these attempts had limited success, and with some very clear recent failures.

The report identified 2 clear reasons why these attempted solutions have failed:

- Foundations “have no biting incentives to reduce application costs”, so platforms have struggled to get funders to collaborate or contribute.

- Charities “shy away from interventions that require an ongoing subscription, or providing payment details up-front”.

Our AI grant writer is a clear solution that doesn’t suffer from these two issues, not only can it reduce the costs, but also help increase access to funding for organisations that have traditionally been excluded.

But to get to that end goal, we need something to be useful right now. It needs to start by working for an individual charity, for their individual grant application.

Why does a charity decide to apply to a grant?

When a charity is thinking about applying to a grant, they usually consider two things:

- What the likely outcome might be

- How much it might cost to apply

It’s usually quite easy to estimate the cost — either as a fixed fee to pay an external consultant, or as the time taken by someone on your team.

But it can be a bit trickier to come up with an estimate for the likely outcome. We can separate the two kinds: rejection or success, but it’s actually a bit more complicated than that. Because sometimes “success” can be bad, and rejection can be even worse than you expect:

- Rejection — most of the time you just get nothing, but sometimes there might also be a damage to the charity’s future reputation with the funder.

- Success — most of the time it’s good because you’ve won the grant, but sometimes it can be damaging: maybe the charity’s application promised work that they were unable to deliver, maybe the reporting requirements were so onerous it destroyed the value of the grant in piles of paperwork, or any number of other reasons

So essentially, the charity is looking to answer 3 key questions:

- What’s the likely success rate of this application?

- What’s the risk that we will miss the mark so badly it damages our reputation with the funder?

- How good would it be if we were successful?

Note: “how good would it be” is less than the monetary value of the grant. Grants are usually restricted funding — funding that has to be spent on what’s applied for. It's not as useful as the “unrestricted” funds that they often have to invest in the application process.

Answering these questions gives you an “expected value” of the grant application process.

To make it worthwhile, this “expected value” must be higher than the cost of applying to the grant. But as charities have limited resources, they also need to make this assessment across all potential grants, and select the grants that have the highest “expected value” once you subtract the application cost.

And those expected values, and costs can vary depending on how you choose to apply.

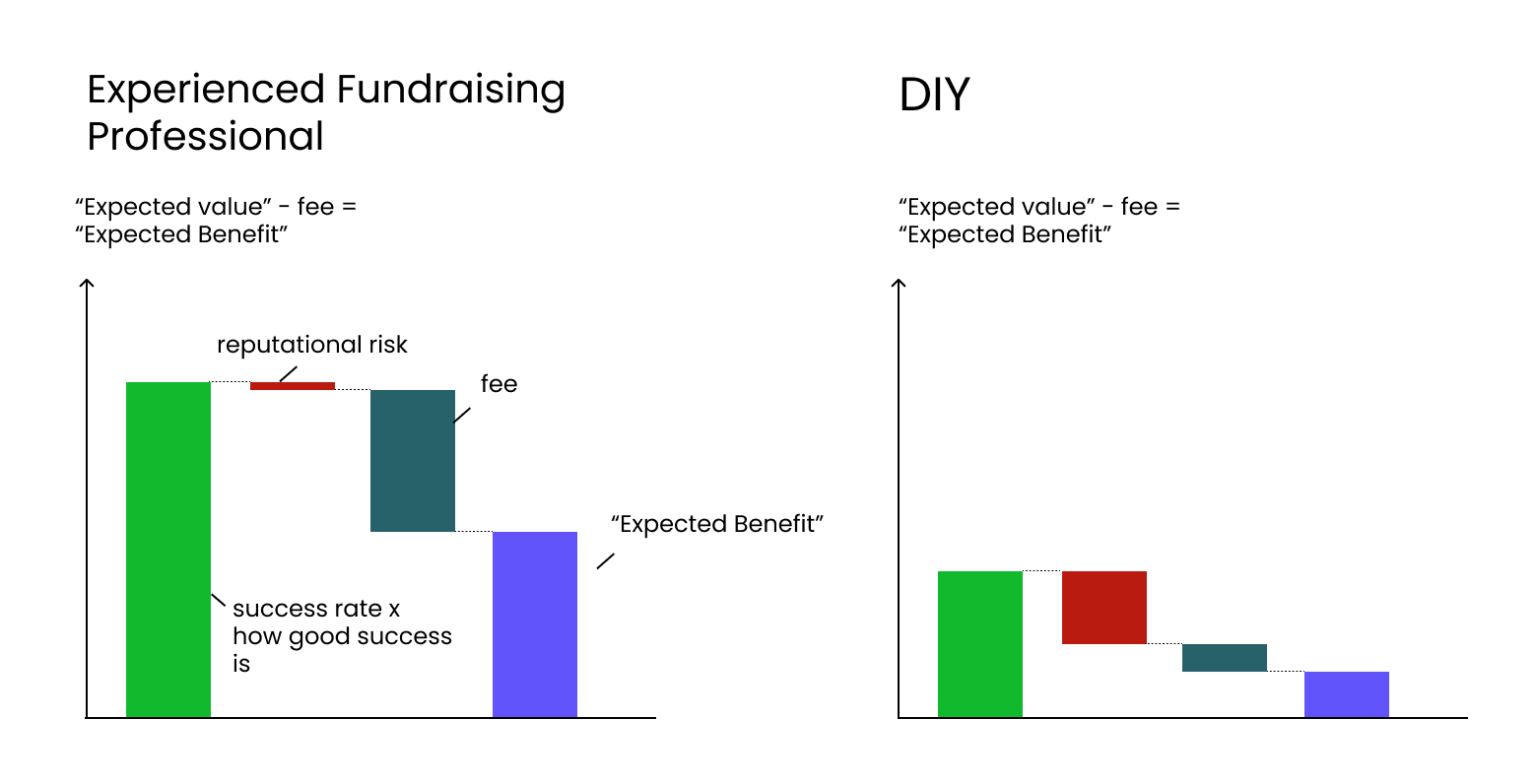

How do charities choose how to apply?

If you’re looking at two different approaches, usually the approach with the higher “expected value” has a higher cost.

For example if you have a fantastic external consultant, you would expect:

- A higher success rate

- Very low, likely 0% risk, of an application that damages your reputation with a funder

- A high likelihood that a successful application will be positive — they are likely to have the inside track on what that funder is like after the application stage, and can help you shape your project plan to avoid over-promising

In return for that service, the cost will likely be quite high.

If you have less experience, or were just doing this in your spare time, it would be the reverse: probably the cost would be lower, but maybe it would be higher risk or you would be less likely to be successful.

Here’s that example on a graph:

So in this scenario, you would probably pick the experienced fundraising professional. You are investing in this process, in the hopes that the investment leads to a higher return down the line. That is the right choice on an “expected value” basis.

For our AI grant writer to be the best and most accessible option for charities, we need to find a way to keep the “expected value” high (by writing high quality applications), while keeping our costs low.

And we probably need to follow the “10x” rule, which says that to overcome the friction in changing the way you do things, you have be in 10x better on one particular axis. In this case, that means 10x cheaper.

How does our platform make this whole process more accessible?

So how do we make sure our expected value high, while making our costs 10x lower?

We start by doing everything we can within the platform to help a charity generate a high quality grant application. We run through a process of using AI to assist with:

- Finding a relevant grant

- Checking whether you’re eligible for the grant

- Drafting a project plan

- Gathering evidence for your application

- Writing a draft of the application

- Reviewing and editing that application

It’s a nice sequence of human and AI working in tandem. At some steps, the AI is doing more of the heavy lifting, with you just steering it in the right direction. In others, we need you to do more of the work, and the AI acts as a guide helping to identify things you might have missed, or things that aren’t clear.

To start with, the AI can help you find a grant. You can just type in some basic information about your project: where it’s happening, how much funding you need, what you think you can achieve and what you’re planning to do. We use that information to check against all the grants in our database, and find you a shortlist of potentially relevant grant funds.

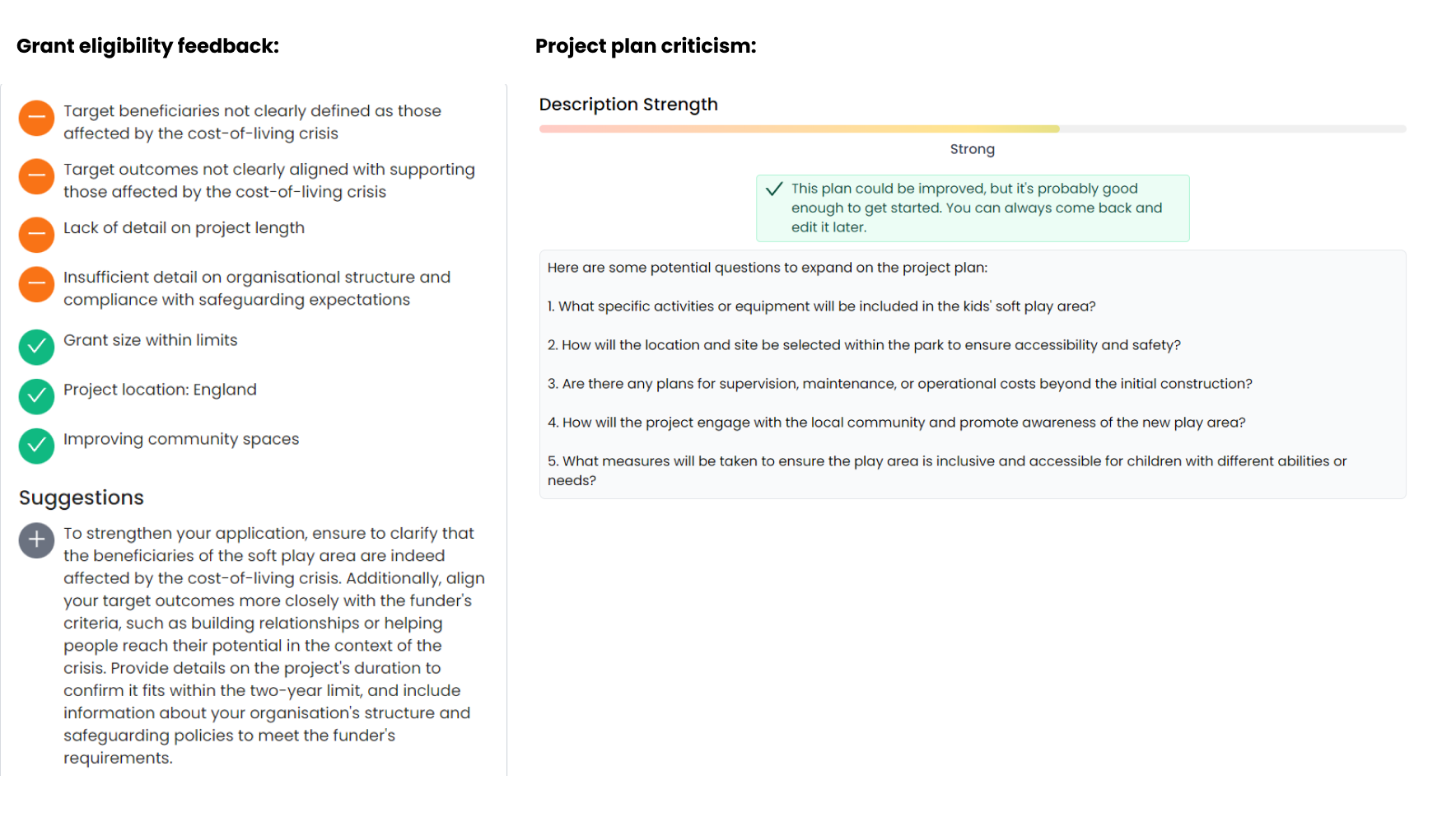

In the next steps, we’ll then give you some feedback on whether the project really is eligible for that fund, and some things you could do to improve the project outline.

Here’s a good example for a pretend project looking to build a new play area in a park:

After this, we’ll need to gather a bit of evidence, otherwise the output will be incredibly vague and generic. If you upload previous grant applications, impact reports, or point us to your website, we can work with that. Part of our special sauce is in how we store that information and choose which bits are relevant to each application question. We’ll even reference sections of the answers back to the sources you’ve provided, so you know the AI isn’t just making stuff up.

To actually write the thing, and to maximise the quality of the application, we use the paid versions of the newest AI models, in combination with the evidence you've uploaded.

Finally, we have options for AI and human reviewers:

- The AI is actually even better at criticising its own work than it is at writing in the first place. You can even get the AI to incorporate its own feedback, by using our “Edit with AI” feature (which also has the ability to increase/decrease word counts, and change the tone of voice the AI uses).

- You can add additional human reviewers, whether that’s board members, someone from a local Council for Voluntary Services or a professional fundraiser.

All that is designed to maximise that “expected value” of an application — increasing the chances you’ll be successful, and reducing the chance you’ll ever send off something you wouldn’t be proud of.

But how much does it cost?

Steps 1-5 above are available free of charge, with absolutely no strings attached. Anyone can create an account on plinth, search for grants, use our AI to check their eligibility, get specific feedback on a project plan, pull together relevant evidence from previous documents and then get our AI to write a draft application for the grant fund. After all we want to help charities get more funding.

If, and only if, a charity is happy with the result of this process, there is then a payment step (without which you can’t copy, download or share the application with others).

This means we don’t get paid unless an organisation believes the quality of our applications to be high enough to be worth using. By exposing all these steps in the process for free, we’ve tried to design the flow of the platform so we can get the largest amount of feedback on the application quality.

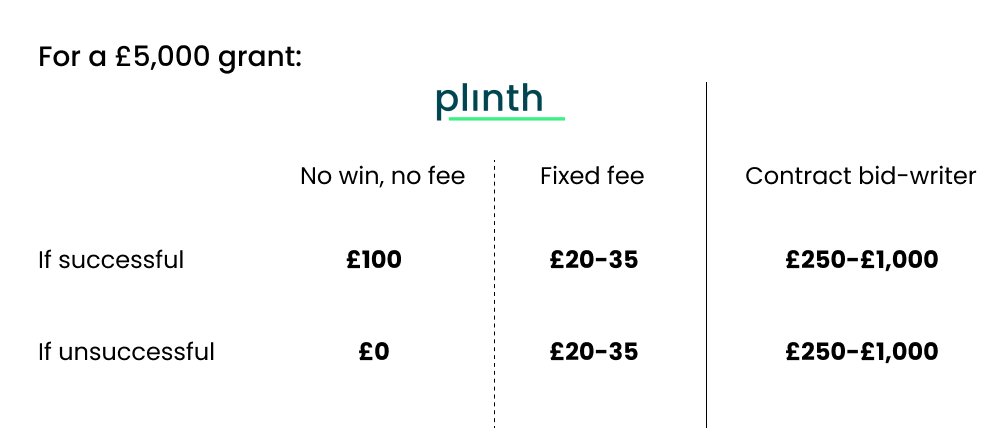

When we first launched, we had a simple flat fee of £35, or a monthly subscription of £50 per month for 2 grant applications each month. In other words, we are at least 10x cheaper than the fee a typical freelance bid writer would charge (£250-£1000), or the cost of a manager’s time to write something similar.

Essentially, we’re aiming to help charities generate high-quality, but low-effort and low cost applications. So every charity can afford to apply for the funding they need to fill the holes in their budgets left from a cost of living crisis, without needing to waste as much time and money on the process.

But recently we decided to go one step further.

Why offer a no-win, no-fee model?

We’re now offering an additional, alternative option to pay nothing up-front, and pay a fee equal to 2% of the grant value if you’re successful.

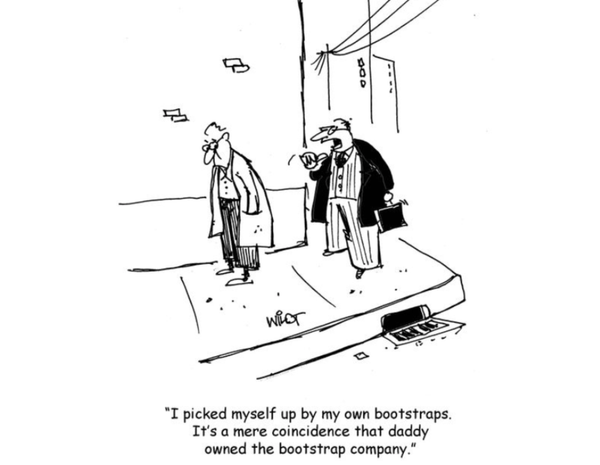

Why is it we’re doing this? Why can’t we just offer this on a low-priced fixed-fee basis?

The main reason is the one quoted in the Giving Evidence report: “charities shy away from things that require an ongoing subscription, or providing payment details up-front”.

Time and again we have found that even the smallest of payments is a major barrier for charities using a new software platform. Even something as simple as needing to work out who has access to the organisation’s debit card can be tricky. And there’s not usually an established mechanism for buying software — because it’s something that’s done so infrequently, if at all.

We’ve spent a large amount of our time across the last 5 years working out how we can offer a comprehensive platform without needing to put a credit card paywall in front of useful features. A no upfront fee approach fits in nicely with the way we offer the rest of our platform — free to use, with no barriers to sign up, and only charging if the organisation is also bringing in funds (e.g. through payments for activities/venue space).

And also, if we want to change the way grant-making works, we need to get as many charities signed up as possible. To do that, we have to remove all the barriers to the process.

Managing risk

But it also makes sense for smaller charities to prefer a no-win, no-fee model, from a risk basis.

While we’ve been explaining fundraising as expected value, most people are risk adverse meaning they are unlikely to go ahead and make a huge investment in fundraising even if it might pay off in theory but, if they get unlucky they could be in serious financial trouble.

Everything we’ve written up to now has discussed “expected value”. But people don’t actually maximise “expected value”. That’s because usually people are risk averse. For example, what if a charity makes massive investments in fundraising that will pay off on an “expected” basis, but then just gets unlucky? The charity may now have much less to spend on delivering their mission, and may even be in serious financial trouble.

That’s the reason why “no win, no fee” starts to sound particularly attractive to smaller charities — who are usually more risk averse because they have less financial buffer to take big risks.

To make this a bit clearer, we thought it would be useful to run through a concrete example.

Take a typical small grant of £5,000, the application cost comparison looks like:

Whether a charity would like to use plinth to apply for a grant, depends on the same answers to the questions we posed above:

- What’s the likely success rate of this application?

- What’s the risk that we will miss the mark so badly it damages our reputation with the funder?

- How good would it be if we were successful?

And the problem is, while we can do our best to make the applications as high quality as possible, our tool is so new that we can’t in good faith make any promises about the answers to those questions.

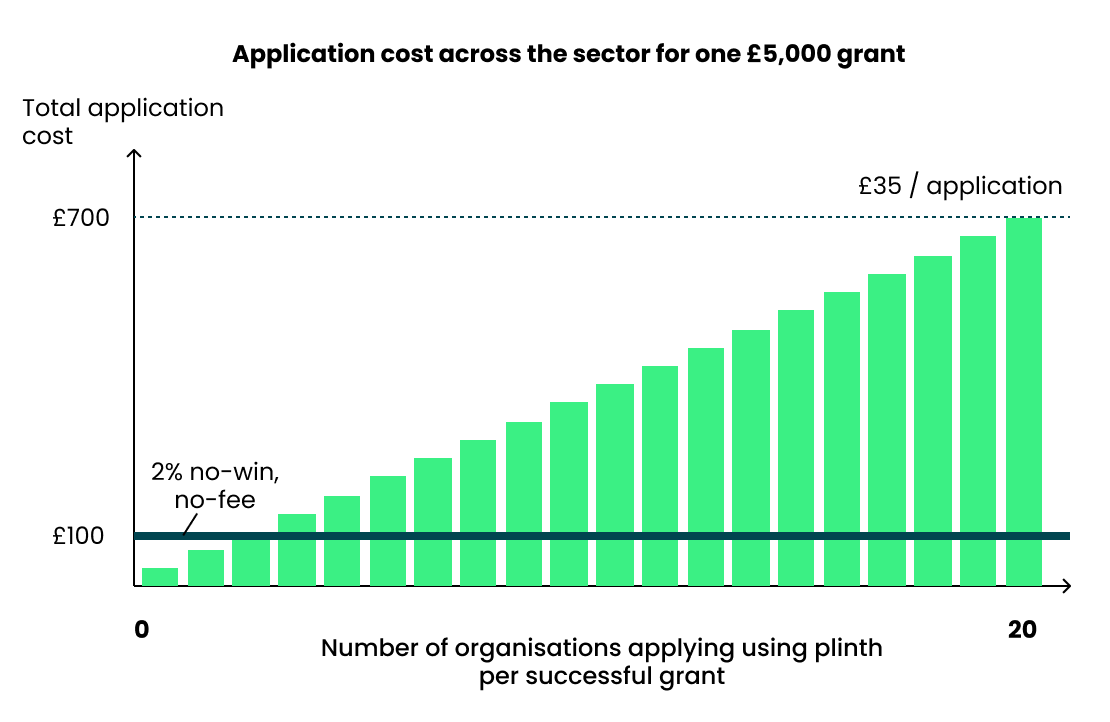

Some funders have success rates as high as 80%+, but others can be much, much lower. If some of the funders with ~£5,000 grants have a success rate of less than 5 or 10%, then even a £35 fee can rack up very quickly — perhaps to over £700 for every successful grant. And that’s assuming those successes are essentially random and our tool is as good as the “average”.

But by offering our tool on a no-win, no-fee basis, we’re shouldering the risk that our success rates will be lower than we hope.

What about the reputational risk? Or the “risk of success”?

Firstly, you should use your own judgment to decide if the output from plinth is something you’d be proud of, and is something you can deliver. And you should be prepared for the success case — you won’t be able to put a 2% fee in the grant budget, so you’ll need to have it available from your other income sources.

But if you doubt your own judgment (for example if you’ve not done many previous grant applications), we’d recommend using plinth in combination with:

- Seeing if your local CVS offers grant application support (some CVSs will also give you free credits to submit applications on plinth, even without the 2% fee).

- Signing up to a fundraising course with someone like NCVO or the Centre for Philanthropy.

- Initially working with a professional fundraiser, either to review an application we’ve helped you write, to apply to a separate grant, or to start from scratch.

That way you’ll be able to judge for yourself much better whether the output you’re getting from plinth is cutting the mustard.

Finally, if you have an extremely high chance of winning a grant, or it is structurally important for your organisation (for example if it makes up a significant proportion of your current turnover), you are likely to be more concerned with maximising the chance of success rate, and be less concerned about the cost of writing the application.

How does a no upfront cost model impact the cost to all charities?

Another reason we think a no-win, no-fee model is a good option is because of the impact it has across multiple charities.

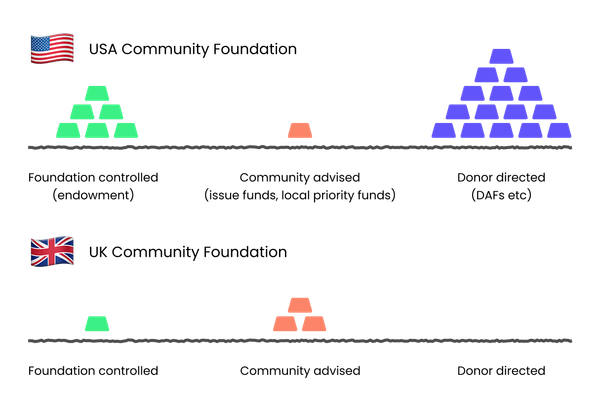

As many people have spoken about, grant applications are getting more competitive. People regularly discuss how only 1 in 15, or 1 in 20 applications are successful, with that success rate continuing to fall over time. This is partly because budgets are getting tighter as Local Government contracts are not being uprated with inflation (and actually this is where the initial inspiration for our AI grant writer product came from).

Charging as a fixed fee means that as this competition increases, if our tool proves popular, we will be charging a constantly increasing percentage of the grant value. We think that would be a terrible incentive to set ourselves, where every additional charity we who applies for the grant, even if they have a low chance of winning, still owes us money. And as an organisation, we’d be sucking up an increasingly large share of funds that should be going to its intended charitable purposes.

Charging on a percentage basis means that even if the competition increases, we’re never taking a larger share of the funding:

This is especially relevant if we’re working closely with a funder, with them highlighting our tool as an option to increase the accessibility of their grant funds. In that scenario, we’re much more likely to have more than 1 organisation applying to a given fund.

Speaking of…

How does it impact the grant application process overall?

Charities are only one side of the grant application matching process. The other side is clearly the funders who decide who to give grants to.

If all we’ve managed to do by decreasing the costs to charities is to increase the cost to funders by the same or greater amount, have we really achieved anything?

Model of a funder

To answer this logically, like we did with understanding the factors that go into a charity making a decision to apply, we need a similar model for how a funder benefits from an additional application.

So again following the Giving Evidence report, there are 2 kinds of grant applications:

- Eligible for the fund

- Ineligible

If a funder gets no eligible applications, that is bad. They won’t be able to distribute their funding. So we can assume that each funder ascribes at least some “value” to receiving their first eligible application.

But what about the 10th application, or the 100th application? There are clearly diminishing returns to each additional application, but if that 100th application is the best/most relevant, the funder should be happy.

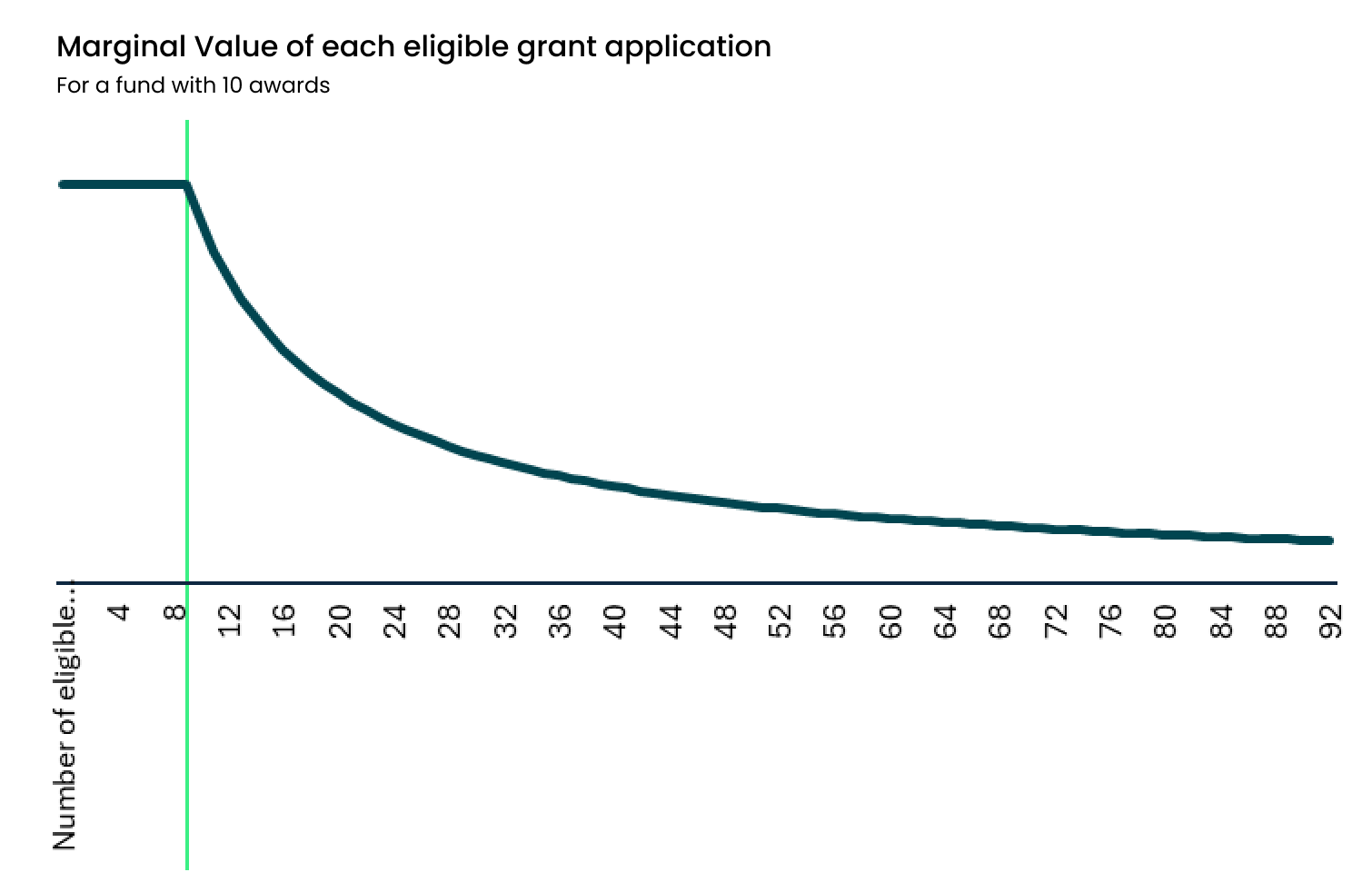

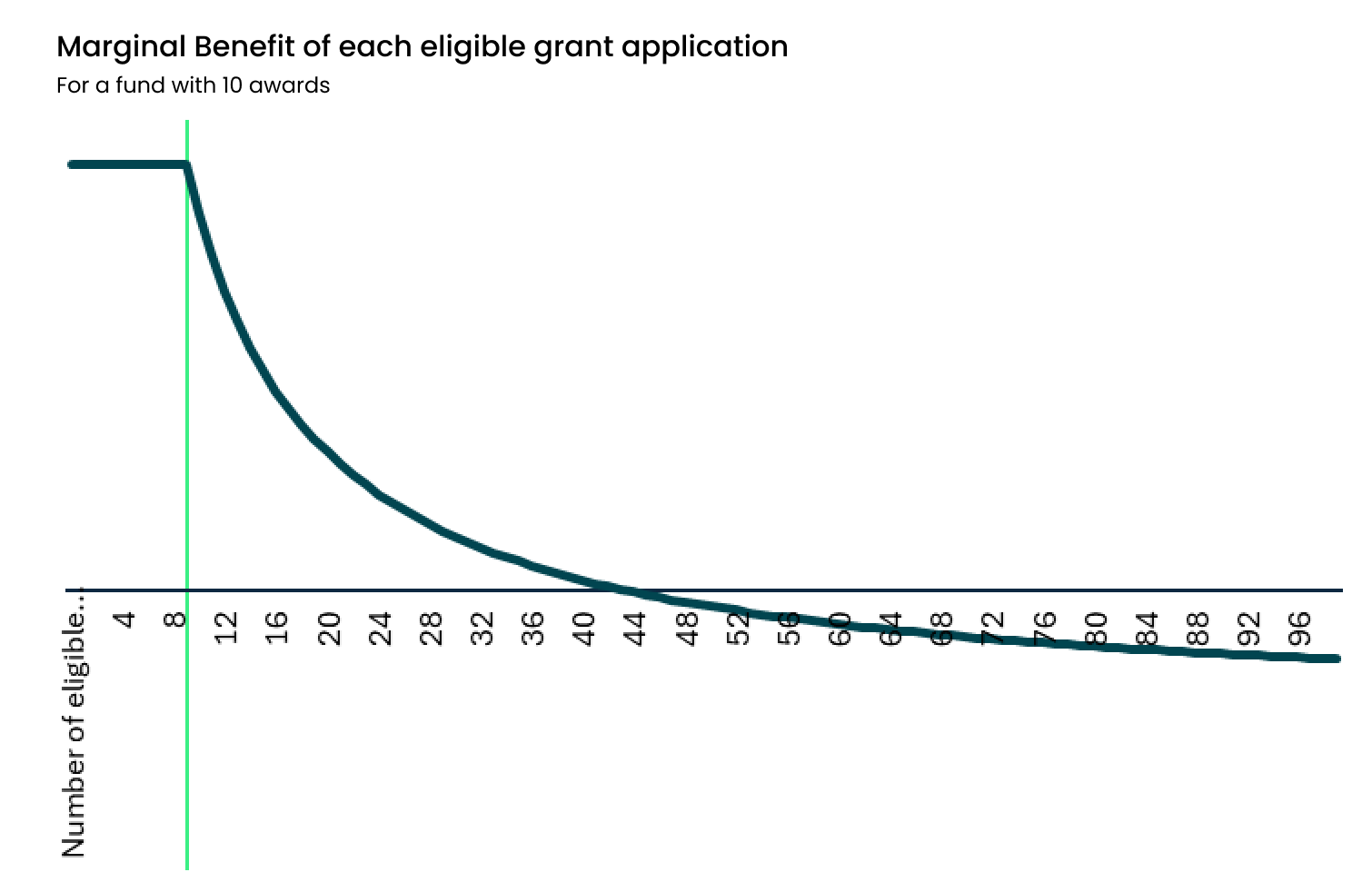

If we have a funder that makes 10 grant awards, we can model more specifically this by asking the question: what is the probability that each additional application would make it into the top 10?

If applications are “similar” and “distributed randomly” (i.e. you don’t know beforehand which are likely to be good), then the probability is quite easy to work out:

- The 10th eligible application is 100% likely to be in the top 10

- The 50th eligible application is 10 / 50 = 20% likely to be in the top 10

- The 100th application is 10% likely to be in the top 10

In other words, for a funder, the 100th application is worth only one tenth as much as the 10th.

We can actually plot it on a graph:

But as well as a value from each eligible grant application, there’s also an administrative cost to the funder.

For each application, there is a cost to review/screen. This is usually greater for eligible applications than ineligible ones (it’s much quicker to bin a nonsense bid than to properly analyse the pros and cons of something that is a good fit). But it can start to add up.

We can model this by asking 3 questions:

- What’s the eligible : ineligible ratio of grant applications?

- How much does it cost to screen/reject an ineligible application?

- How much does it cost to review an eligible application?

Once we have answers to these 3, we can then model the marginal cost of each eligible application to the funder. We can then subtract the marginal cost from the marginal value, and get the “marginal benefit” of an additional eligible grant application.

And then we can plot it on a graph!

This is a graph showing a funder with quite high screening costs (as high as 20% of the value they get from an eligible application), and with a fairly reasonable eligible : ineligible application ratio of 5:1.

What you can see is that in this toy model, the benefit of an additional application actually goes negative once you get past 45 or so applications.

Obviously all these actual values are just illustrative (because funders rarely measure their own costs for this process), but it gives us clear logical questions to answer on whether our AI tool is going to be net beneficial or damaging to funders, which are:

- How many eligible applications are funders receiving at the moment? Where are they on this curve currently?

- Is our AI grant writer going to change the eligible : ineligible ratio?

Where are funders on the curve currently?

Unfortunately there is no one correct answer to this. Some funders are hugely oversubscribed (e.g. UK Youth, who were 10x oversubscribed in just three weeks). For these funders, it may be the case that they’re already into the “negative marginal benefit” territory. These funders likely will find our AI tool a bit annoying initially, even if it’s submitting high quality, eligible applications. They’re simply just overwhelmed already.

But it would be a mistake to assume all funders are in the same boat. In one survey of the sector, 2 out of 3 funders didn’t disburse as many funds as they intended, partly due to not receiving enough eligible applications. And many funders have high success rates and are very actively seeking more applications from eligible projects charities. For example, Kent Community Foundation, who have a 67% success rate, and have a specific strategy to “continues to deliver its outreach programme to attract new local causes”.

Generally speaking, funders with more specific eligibility criteria, whether that’s because they have a specific local remit, or very specific themes that they want to fund, are more likely to be actively seeking new applicants.

Will we be changing the eligible : ineligible ratio?

Are the applications that we help charities write going to be more or less likely than average to be eligible for the grant?

We don’t know for sure yet, but we have some indicative evidence from previous research.

According to the Directory for Social Change, “funders with eligibility checkers received fewer ineligible applications: 10% vs 21% across all funders”. But many funders do not have eligibility checkers — they can be difficult to build, and hard to get right when the criteria are a bit fuzzy (like whether you work with a target demographic, rather than your previous year’s turnover).

Fortunately, our platform now provides an eligibility checker for every funder, that can even understand the fuzziness inherent to the sector. All they need to do is have their criteria in text somewhere on their website, and we’ll do the rest. This means we’ll be able to quickly and effortlessly surface even the small things that would might make a charity ineligible, and prevent them from wasting their time and effort.

We believe this means applications generated with our platform will likely actually have a higher eligibility rate than average.

What is happening already?

If we’re looking at the ratio of eligible to ineligible applications, and their quality in general, we shouldn’t ignore the fact that things are changing quickly already.

According to a recent survey, 35% of charities are already using AI for certain tasks. No doubt many of them are using it for bid writing, given how annoying and costly a task it can be.

As we’ve described at length, we’ve invested a lot of time and effort into getting our AI to write higher quality applications that are relevant to funders. It didn’t work naturally with the models out of the box, and it wasn’t possible to do with the free versions of the AI platforms (we tested that extensively).

But with the free versions it was very possible to create something passable at first glance. It would typically speak in vague assertions, and fill paragraphs of text with only 1 or 2 bullet points’ worth of content.

We have no doubt that as use of AI becomes more prevalent, if it leans towards this non-specialised /non-trained version, it will cause a significant increase in the number of irrelevant or low-quality applications. This will definitely increase the administrative cost for funders.

We hope we can prevent this by offering an easily-available and affordable alternative.

Changing the incentives

In some senses it’s quite funny that we’ve just spent a long time talking about minimising funder costs. Because it’s not actually something that funders normally worry about.

In that same Giving Evidence report, it discussed at length how (paraphrasing) funders often don’t know or don’t care about the costs associated with grantmaking. They had a particularly pithy quote: “The problems of philanthropy are not experienced as problems by the philanthropists (Katherine Fulton)”.

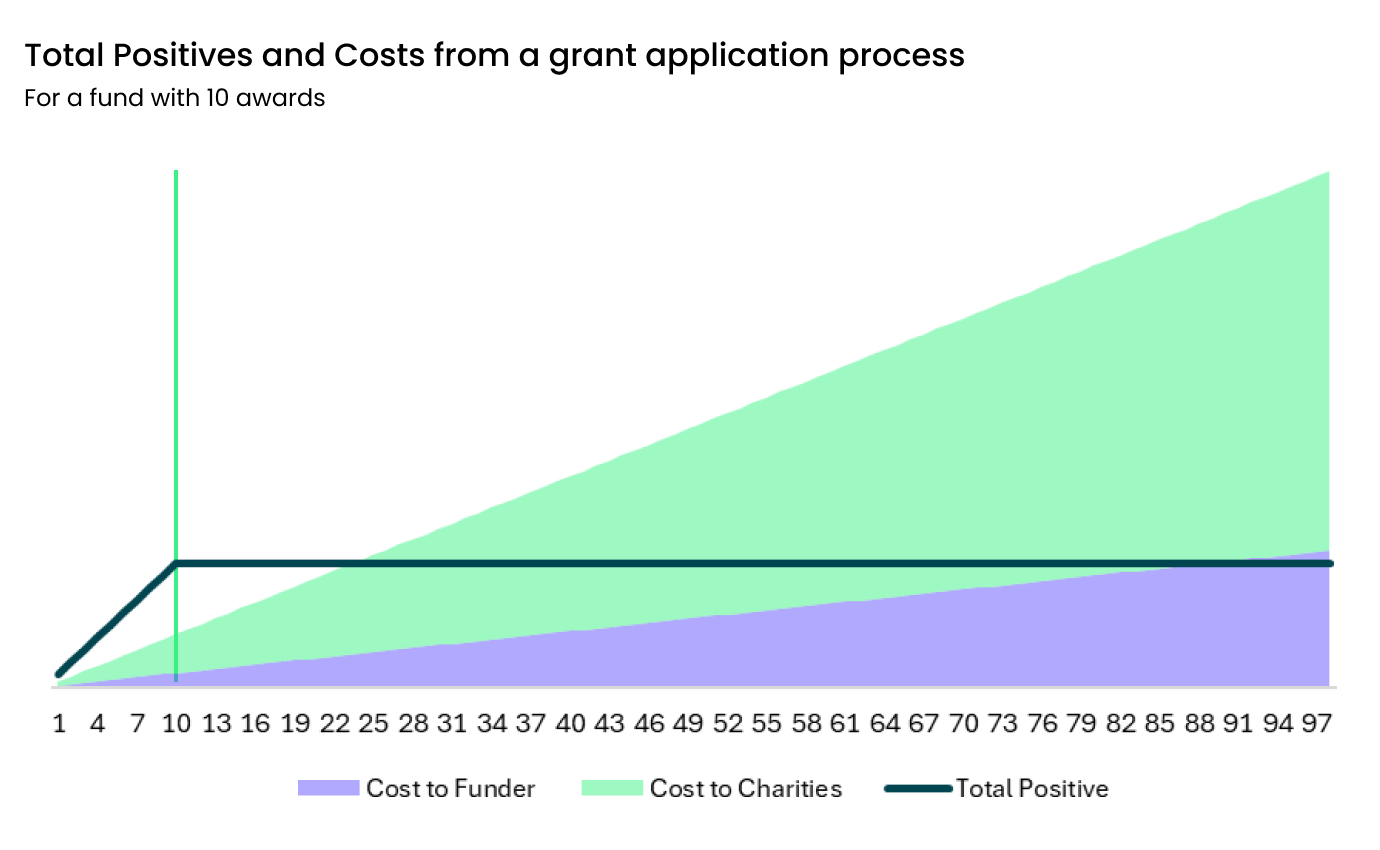

With two last graphs, we can show the problem by plotting the Total Benefit to the world as well as the cost to charities and funders against the number of grant applications received:

Long before the costs to the funder get particularly high, the cost to charities has already exceeded the total value to society (echoing back to our piece from 5 years ago).

And unfortunately, those costs are often not very visible to funders, so they don’t do much to address them. They have no real incentives to. And often funders will “show off” how many people they have applying to them:

- “NatWest aimed to attract many applications – only to then reject 93% of them.”

- “A programme by Aviva solicited five times as many applications as it could fund”

- “The Cabinet Office had to reject 98% of applications”

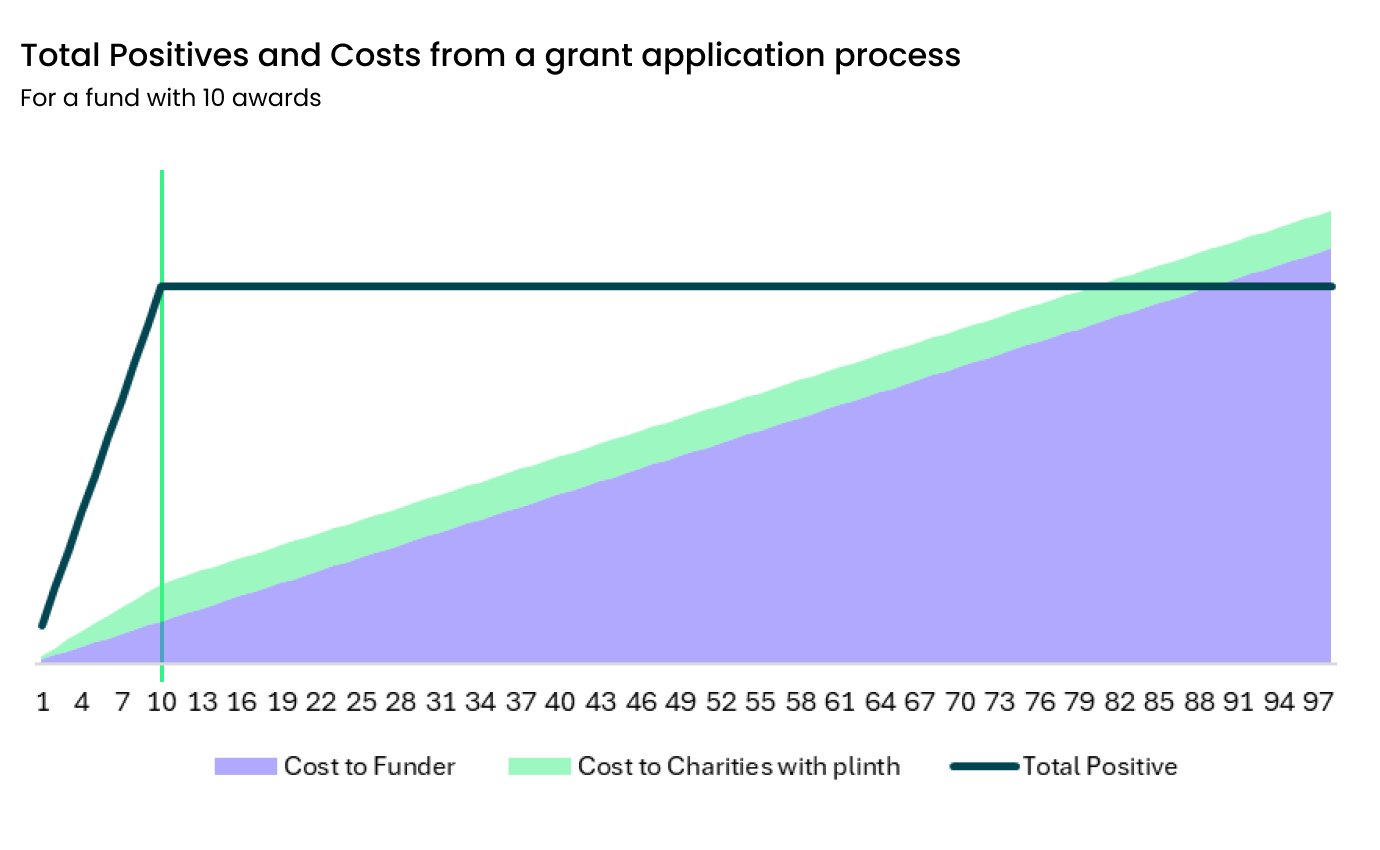

Using plinth, we’re not only reducing costs for an individual charity, we’re also capping that fee to 2% of the grant value. That means the “cost to the funder” is now much closer to becoming the “biting constraint”:

What does that mean? It means funders will need to make decisions on how many applications they should be aiming for based on their own costs — not costs to someone else that they can choose to ignore.

And thanks to our eligibility checker, they can do this easily, by simply tightening their eligibility criteria, and we’ll automatically pick it up and use it to screen potential applicants.

Conclusion:

There’s a lot wrong with how grant-making works currently.

We believe our AI grant writing tool can help fix a lot of the problems. We think we can reduce the application burden from the 17.5% it currently costs small charities, asymptotically towards 2%.

To do that, we’ve tried to build it to write high quality applications, with a low or 0 upfront cost.

This working depends on the quality, and specifically relevance, of the applications it helps to write.

If you think this sounds like an interesting approach, please do try out the platform. We hope you like it, and if you can give us feedback on how we can improve the ease-of-use, or the quality of the content, please let us know.

Thanks,

Tom