Why I'm proud to be a charity case.

Often we're told that to be a 'charity case' is a label of shame. That it's one of pity and dependence. But the truth is, our outcomes and life experiences are contingent on our dependence on the generosity of others.

It was charity in the broadest sense, that afforded me the life experiences which developed my most important skills and helped me reach my potential.

I am incredibly grateful for this and I think it's important to tell this story.

My great grandmother was born in Trinidad in the 1910s under the British colonial system of indentured servitude. Her poverty-stricken conditions denied her the opportunity to learn to read or write and so, became an expert in the domestic domain, creating a loving family of nine instead. Christian missionaries then came along to build free schools which afforded her daughters that missed opportunity, allowing my grandmother to be educated until the age of 12. Unlike her mother, her minimal education meant she possessed tools that unlocked experiences outside of the home, eventually opening her own corner-shop whilst raising her daughter. My mother continued this gradual progress, completing schooling until the age of 18 - which afforded her even greater opportunities, eventually leading her to London. The baton was then passed to me and despite the single mother, inner-city London, state-comprehensive upbringing - I was able to graduate from the University of Oxford with a degree in Philosophy, Politics and Economics.

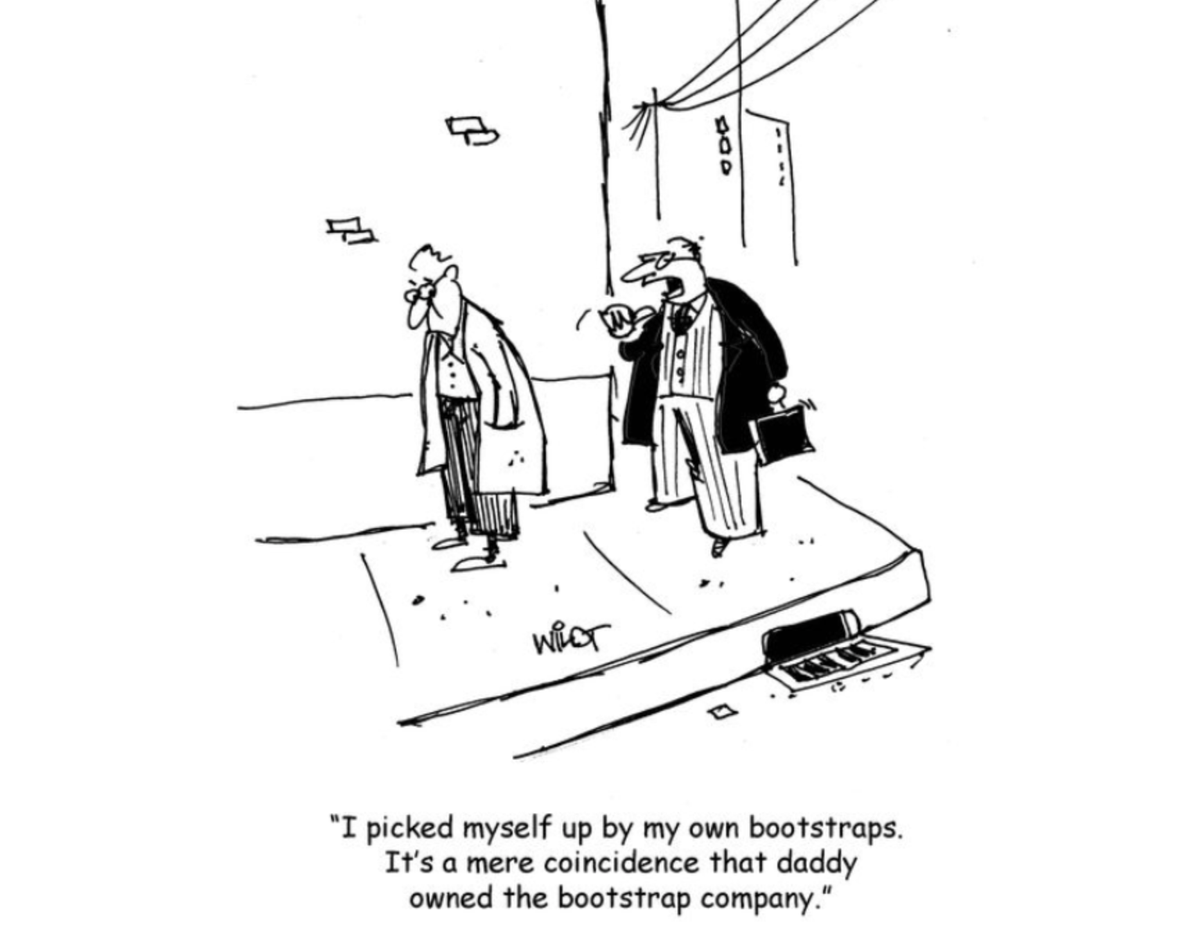

This might look like a classic tale of grit and determination - a story of someone who beat the odds. Indeed, in today's world, where meritocracy and individual 'hustle' are celebrated, I'm often sold the idea that I am a self-made man. That the story of my success is attributed to my hard work, resilience and drive. This worldview perceives 'beating the odds' as a story of the individual as if it is the child that raises themself and not the village.

And yet, it never ceases to amaze me how popular this view remains, despite its superficiality. Individual virtues and the ingredients for 'success' are not formed in a vacuum but through the charitable acts of people and our communities. This is the ultimate force which turns unrealised potential into lived opportunity.

None of us achieve anything alone

To really understand how charitable intervention is the ultimate force which helps individuals realise their own potential, I think it’s important to make a distinction between the different types of dependencies that can affect and determine individual outcomes.

The first and foremost type of dependency is personal - e.g. your family and friends. I think this is the most widely understood dependency type. Your family circumstance is arguably the defining factor for individual outcomes. If you are born in a rich family, you'll likely inherit a lot of wealth. If you are born in a loving and nurturing family, you will likely develop much more positive characteristics and traits. Similar logic can be applied to your closest group of friends. We form dependencies on those around us and the extent to which they form a viable support network can affect our outcomes. Thinking about my own family's history, the legacy of indentured servitude definitely makes me relatively disadvantaged in a material sense. However, the generational love, commitment and generosity from my great grandmother that flowed to me, undoubtedly helped form whatever virtues I possess.

The second type of dependency is societal, which can be split into two categories - governmental and communal. Governmental dependency is often taken for granted but it is worth highlighting that it forms the very structure that determines the extent to which we flourish as human beings. For example, my attendance at state school gave me a sufficient level of education aligned with societal standards. Comparing this to the colonial structures imposed on my great grandmother that denied her education, then it is clear how essential it is for individual outcomes.

The most interesting of all though is communal dependency. This is the layer that exists above the foundations of personal and government dependency and is where charitable intervention comes into play. It is charities which best embody this principle. After all, they are groups of individuals who come together to resolve or alleviate the problems within a community. For example, irrespective of their intent, it was the charitable intervention of Christian missionaries that boosted the literacy rates for my grandmother and her generation across the Caribbean - helping to overcome the educational disadvantages she faced - which were ultimately cultivated by preexisting circumstances (colonial structures and their impacts on her family.) Charitable intervention is therefore crucial in either building upon or helping overcome the circumstances one is placed in. It is the ultimate mechanism that allows the individual to reach their full potential.

Understanding that the individual is formed by these different dependencies, knowing or unknowingly, obliterates the myth of the ‘self-made’ man. And yet, we still levy the condescending ‘charity-case’ accusation at those who have experienced that extra benefit of communal dependency.

Truly, I find this bizarre - given that in my own experience, it’s evident none of us achieve anything entirely alone.

How charity made me who I am

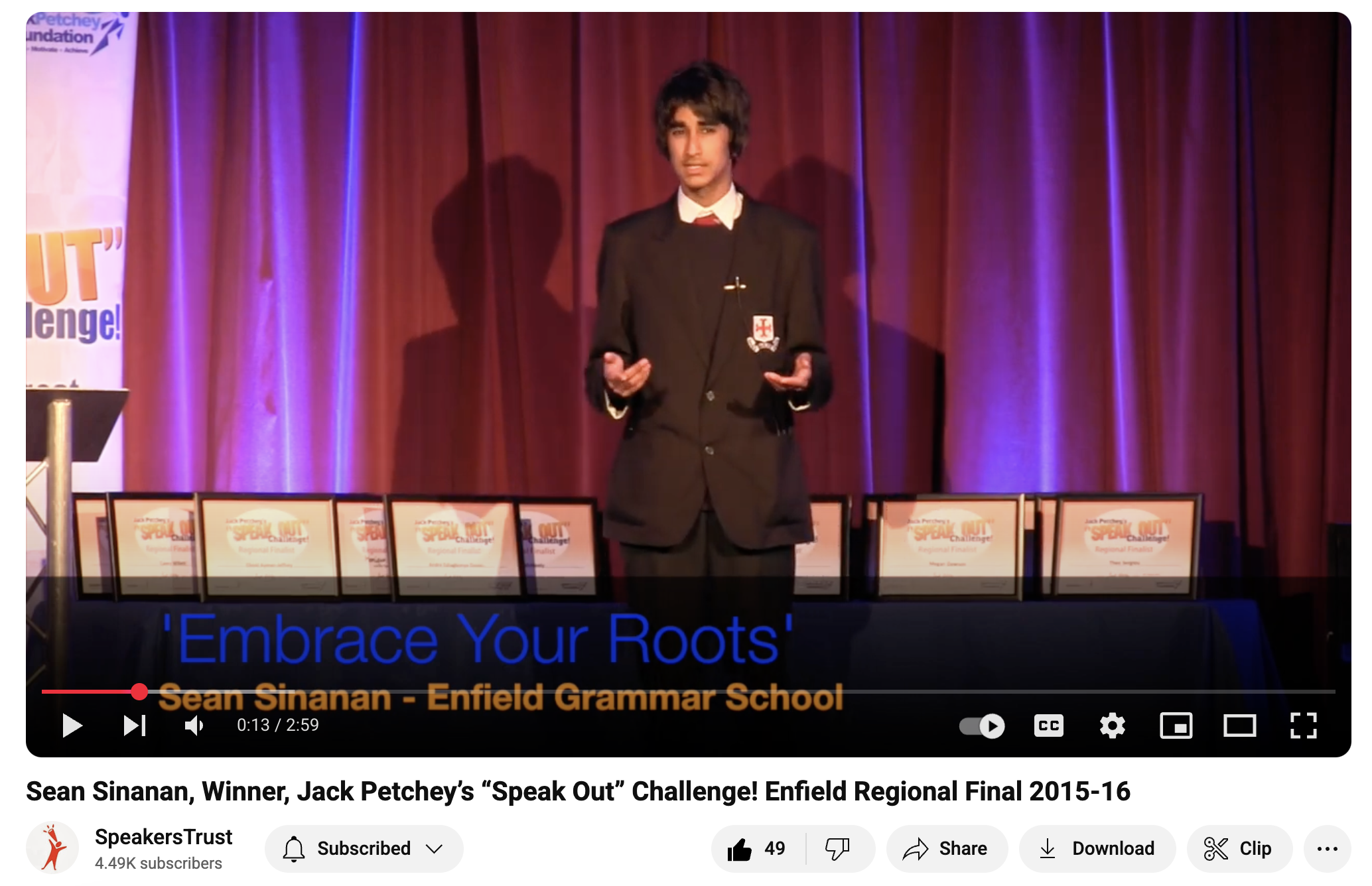

In my early school years I first developed a natural intrigue in politics. My teachers noticed this and pointed me to the Youth Parliament, a development program now funded by the National Youth Agency charity. This experience introduced me to youth workers who saw something special in me and motivated me to develop my skills in debating and public speaking. Pursuing this advice, by the age of 16 I gave a televised front-bench speech at the House of Commons and spoke about youth justice on BBC radio, TV and in the London Assembly. Alongside this, I also became aware of the Jack Petchey Foundation and the Speakers Trust - charities which run a popular nationwide public speaking competition. Having won this competition it led me to receive mentorship that grew my confidence, public speaking and social abilities.

When it was time to think about University, it was charitable social mobility programmes that even introduced me to Oxford. Schemes run by the likes of the Social Mobility Foundation, Sutton Trust, Target Oxbridge and UNIQ made me think such a feat was actually possible. A grant from the Enfield Charitable Trust also paid for me to experience a prestigious summer school where I learned the basics of philosophy, politics and economics in France, an opportunity I could have never afforded otherwise.

Without these charities, such opportunities would have never been possible. I never had any connection to these prestigious institutions like Parliament or the BBC, let alone Oxford. My circumstances developed my raw skills and ability, but it’s clear it was charitable intervention that allowed me to fulfil this potential. For that reason, I’ll always say I’m a charity-case with pride.

A badge of honour

I wonder then, what does it say about our shared values as a society when we elevate the status of the 'self-made' individual but undermine those who are charity-made?

The act of charity is a cornerstone of the human experience and so long as we uphold this illusion of being 'self-made' I think we do damage to our understanding of how valuable charitable intervention is in our own formation. Recognising this shouldn't undermine agency or personal achievements but deepen our gratitude and reinforce the importance of building systems and communities that allow more people to thrive.